Flood to Shinar

This is part 3 of the The History of the World Series

; Introduction is part 1.

Click here to read in series

A Biblical History of the World

In accordance with all known secular histories

PREFACE

There are two types of histories; those which follow the narrative of evolution, and write the history of civilization as a long, slow, crawl from knuckle-dragging troglodytes up to hunter-gatherers, nomads, villages, city states, and empires; these sources are well-funded, and have access to an immense amount of facts from ancient civilizations to support their narrative.

Then there are those who follow the Christian narrative, believing in a literal, world-wide flood about 4,300 years ago, give or take, and who try to tell the story from that point. Unfortunately, and I mean this in the nicest possible way, most of those histories are laughable.

They take a few points of agreement with the Bible, and spin fanciful theories that are poorly supported by facts largely because the sort of authors who write such histories are not usually academics, and frankly know very little about the history they are trying to explain.

I intend to try and write a middle ground; a seriously researched and scientifically supported history that begins with the Bible, but which fits the evidence of Egyptian, Assyrian, Sumerian, and any other relevant civilizations into the story in its proper place without dismissing or rewriting either story.

Believe it or not, this is pretty much a unique goal in the world. Christians are generally willing to play fast and loose with the facts, and you would not believe the way historians dismiss, rewrite, and ignore ancient sources in order to arrive at the conventional timeline. It’s truly mind-blowing, but we’ll have plenty of time for that later.

Writing a history that actually reconciles all these sources is, as you might expect, a tall order. But after extensive research I’m convinced that an honest reading of Egyptian and Sumerian history demands the Bible’s timeline, and cannot be stretched out over 10,000 years without immense wishful thinking on the part of historians.

In the end, you, the reader, will believe what you want to believe. If you want to believe God does not exist and that the flood was a myth, this will not change your mind. But if you want to believe that the Bible is true, this history will give you good, scientific reasons to feel comfortable about your choice.

It is difficult to be a Christian in a world which worships science – never mind that the science is continually shown to be a victim of group-think. Because when every educated and respected person tells you as an absolute fact that, there are 5,000 years of recorded Egyptian history, plus thousands of years of prehistory, you want to say “that’s not what the Bible says”… and yet you’re really not qualified to have an opinion unless you’ve wasted absurd amounts of your life reading the science yourself.

That’s why this book exists; to show you that, yes, the history sounds good as a package. But when you take out a magnifying glass and inspect it, read the sources, listen to the academics debate amongst themselves in unnecessarily big words, you’ll find they don’t agree about literally anything except that they, as a group, are right and we, the Christians, are naive morons.

Blind faith is, indeed, foolishness. But my goal in this book is to convince you that it requires more faith to believe in traditional history than in the Bible’s version; that the story of evolution requires more faith than the creation of God.

You’re about to read the story I believe in. It’s not correct; broadly, the story leaves out entire civilizations and the dates provided are, in some cases, probably off by half a century or more. But it is a narrative that ties in with the Bible’s version at every point, and, most importantly to me, does so without rejecting the immense wealth of tablets, histories, and witnesses of ancient history.

When read without prejudice, those tablets support the Bible’s version at every turn. Indeed, in many cases it takes a lot of effort to massage the ancient records into the official narrative we are taught in schools.

So read the story, and then decide which version requires more faith; belief in God… or belief in an extraordinarily, incomprehensibly, unimaginably lucky chaos which started with rocks and somehow created Taylor Swift. And baby shark. So, mixed bag.

A NOTE ON DATING

Adam was created in 3971 BC. This date differs from what everyone else believes, by at least a bit, but it is broadly agreed upon by everyone who believes there was such a person as an actual Adam. I arrived at this date by two independent lines of reasoning; first, that it is exactly 4,000 years before the death/resurrection of Jesus (not His less-significant physical birth, as followed by most chronologists).

The significance of 4,000 years involves a 7,000 year millennial “week” plan of God (Daniel 9:27) and Jesus being killed in the midst of that week, which based on other versions of this symbol, meant “he would be killed in the end of the fourth (thousand-year) day,” i.e., 4,000 years from creation.

The second way is by adding up all the dates in the Old Testament; there are about a half-dozen hinge points in Biblical chronology, places where you can plausibly tie a date to an event at 75 or 85 or 99 years in Abraham’s life, for example, and if you make the right choice – which, in retrospect, is usually the obvious choice – it adds up to 3971 BC. Since it’s thus supported in two ways, I’m quite confident of this date.

If you’re interested, the Biblical basis for these choices is laid out in the appendix. Going forward, rather than say 2312 BC every time, I will simply use ‑2312 to indicate BC dates.

Telling the history of the world is necessarily about the stories of the people who created history; however, to accurately place those stories in context in relationship to each other, a good history must necessarily also be about chronology; how long before or after something happened someone lived, that sort of thing.

Since it also needs to place people in their proper environment – Jesus being laid on an adobe bench in a caravanserai, not in a wooden hay manger in Germany – this will also necessarily be about geography, and of course about the cultural habits of the people who lived in that region.

But the focus will always be on telling the story of history. As if, around some campfire, you were explaining to your kids what happened in the beforetimes; only, you know, tell them what actually happened, not a ghost story.

NOAH’S ARK

According to the Bible, Noah and his three sons and their wives – eight people in total – survived a global flood which “covered all the high mountains.” Modern historians, loath to believe an ancient book, dismiss this as a local flood which impacted only Mesopotamia; yet there are global flood legends in almost every culture around the globe, from Peru to Japan, Greece to India.

To an objective observer, this strongly argues that our remote ancestors remembered a flood that impacted all of them, not merely the Sumerians. Unfortunately, as you will see in this book, historians are not the objective observers they would like us to believe they are.

There is considerable geophysical evidence of a universal flood; fossils buried across multiple strata, enormous layers of solid rock folded without cracking suggesting they were still in a putty-like state when the land buckled; so many things I could mention. But there are many books devoted to those things, and this is not one of them. Our focus is on written history, not geological history.

So our story begins in the aftermath of that flood, when there begins to be recorded history; not only in the Bible, but in Sumer as well. The flood, according to the Bible, began in the year ‑2314 when Noah was 600 years old. Warned by God to build a giant boat beforehand, he spent upwards of a year in the ark with his wife, three sons, and their three wives.

Meanwhile in the epic of Gilgamesh, the hero travels to a far land to find the secret of immortality from Utnapishtim/Ziusudra, who tells him of how he survived the flood – making him the equivalent of Noah.

In Gilgamesh’s version, many of the same elements are found; a divine warning, a massive boat saving all the animals, resting on a mountaintop, sending out birds, a sacrifice after the flood on the mountain, etc. Many differences too, reflecting different narrative goals (Gilgamesh makes God the bad guy, for example). Still, enough to show a shared cultural memory.

When the flood waters began to recede, the ark rested on “one of the mountains of Ararat” (Genesis 8:4), this in the year ‑2313. We know from the flood story that it took three more months for the other mountains to be visible (Genesis 8:5), meaning that the mountain upon which Noah rested was the tallest mountain in the region.

Greater Ararat is the highest peak in Turkey and the Armenian highlands with an elevation of 5,137 m (16,854 ft); Little Ararat’s elevation is 3,896 m (12,782 ft). (Wiki, Mt. Ararat)

This agrees well with the mountain known today as Mt. Ararat, specifically Greater Ararat. There have been many claimed sightings of the ark or its remnants on or near this Mt. Ararat over the years; no conclusive proof has ever been brought forth, but many anecdotes, both in modern and classical times, place the resting place on that site.

It’s important to note that the Bible did not call the mountain “Mt. Ararat” or give it any name. It was simply a mountain in the territory of Ararat, which referred to the region known in antiquity as Urartu (same word, different vowels/spelling).

There is no indication in the text that Noah or anyone else named the mountain at the time. This will become significant later.

THE FIRST MIGRATION

The first recorded thing Noah did upon leaving the ark was offer a sacrifice, and secure a promise from God that there would be no further floods to destroy all mankind (Genesis 8:20-9:17). God promised never to bring another global flood, and He hasn’t.

The fact that we’ve had innumerable damaging floods around the world since then argues strongly that they do not violate God’s promise and hence, that the flood of Noah was indeed global, never to be repeated.

The second thing Noah did, at least that we know of, was to plant a vineyard (Genesis 9:20). I guess being cooped up with his family for a year in a floating box full of stinky animals made this a priority. But grapevines don’t grow well at 16,000 feet; nor does much of anything else.

Meaning that Noah must have left the ark and descended the mountain, the foot of which rests at about 4,000 feet above sea level. Having done so, would he stick around in that general area or move farther afield?

At first you’d think that staying near the ark, a handy source of building materials, would make sense. Then you remember that the afrk had settled near the top of a 5,137 m (16,854 ft) mountain! The labor saved by recycling the wood can hardly be justified by the effort to climb up there 12,000 feet above the base to get it.

Besides, in the aftermath of the flood there would have been piles of driftwood everywhere. Wood was hardly a scarce resource. So without the ark, there was literally no reason to stay around Ararat. Was there a reason to leave?

Today, the winters there are cold and summers are relatively short. In winter it often doesn’t rise above freezing for months at a time. Not only is this unpleasant, it makes preparing food and keeping animals alive difficult.

Because of the global stirring of the ocean by the flood, the climate was certainly different, probably warmer at first; still, from the latitude and the altitude alone, it would have been a cold rocky place, not well adapted to “being fruitful and multiplying.”

So Noah would have been encouraged to find a new home in a better climate; one at a lower elevation with soil better adapted to farming. But where? The easiest way to move through new country is to follow rivers or coastlines; they provide a constant source of water and food.

So looking at this topographical map of the area, there are two options; the closest is to move east, towards the Armenian lowlands and the Black Sea. They may indeed have done this for a few years, since lowlands start immediately behind Mt. Ararat. And it is decent land, but still quite cold; it’s also mostly semi-arid and bounded by the Caspian Sea – with no good expansion beyond that point.

To the east across the sea is pure desert in Turkmenistan; to the south is a narrow strip of good land backed by mountains in northern Iran, behind which is forbidding desert for thousands of miles. These limitations to the land do not make it a good place to obey God’s command to “increase abundantly in the earth, and multiply in it” (Genesis 9:7).

The other option is to move west, following the headwaters of the Tigris and/or the Euphrates. Doing this, you abruptly leave the Turkish highlands and descend into the upper Euphrates basin in what is now northern Syria and southeastern Turkey.

This is flat, wide, well watered, and fertile land full of game. A perfect place to multiply – and a great place to plant a vineyard. Now when the Bible records the story of Noah’s drunkenness, Canaan had already been born and was likely an adult since he was cursed by Noah (Genesis 9:20-25).

This places the event no earlier than 40 years after the flood, likely later. This allows us to place the story of Noah’s vineyard not at Ararat, but with a fairly high probability in southeastern Turkey. It’s one of only two places they could have gone from Ararat, and the one that makes the most sense.

…And isn’t it interesting that science and the Bible intersect at exactly this point; for the oldest monumental creation, the first evidence of true civilization known to modern science, is Gobekli Tepe; and it’s precisely where we would expect Noah to have settled after the flood.

GOBEKLI TEPE

I expect to expand this section considerably after visiting the site in person this year, but for now I can rely on Wikipedia to give you reasons to believe this was the site of the first settlement after the flood.

Göbekli Tepe was built and occupied during the earliest part of the Southwest Asian Neolithic, known as the Pre-Pottery Neolithic (PPN, c. 9600–7000 BCE). Beginning at the end of the last Ice Age, the PPN marks “the beginnings of village life,” producing the earliest evidence for permanent human settlements in the world. (Wiki, Gobekli Tepe)

It’s interesting that the first place we expect “the beginnings of village life,” happens to be precisely where modern scientists likewise place “the earliest evidence for permanent human settlements in the world.”

If the Bible is simply a late Babylonian concoction written to justify Jewish occupation of the land of Canaan, as is widely believed by academics, we wonder how they managed to guess that the earliest human civilization came from exactly this location.

If it were pure chance, with no real knowledge of the facts, why didn’t the ancient Jews place their ancestors somewhere else in say, Assyria or Egypt? And if they were simply making stuff up, a far better propaganda would place the earliest humans in Jerusalem, with Mt. Zion as the site of the landing of the ark. I mean, if you’re making up stuff, make up stuff that helps your cause!

Before this book is done, I will challenge your ability to remain a skeptic about things like this. In fact, let’s do it again right now. If the Bible is correct, all land mammals and most birds began to spread over the earth from this one point.

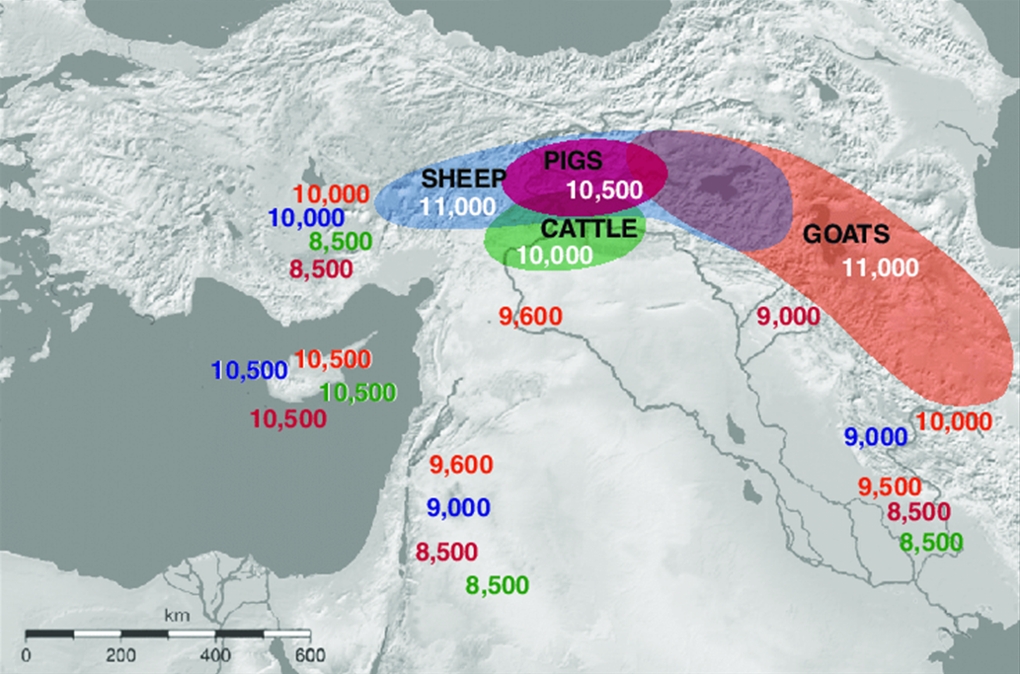

So it is quite gratifying that modern science confirms this is true – at least of domesticated animals; this would also be true of most domesticated grains. And as it happens, this is exactly what science tells us.

“The origin and dispersal of domestic livestock species in the Fertile Crescent. Shaded areas show the general region and the approximate dates in calibrated years B.P. in which initial domestication is thought to take place.”

“Genetic studies have subsequently ruled out European ancestry for domestic wheat, barley, and pulses, confirming the Near East as the source of these crops” (26, 39). Morphological, cytological, hemoglobin, and, most recently, genetic studies have shown that the ‘‘wild’’ sheep and goats found on Mediterranean islands, once argued to be the descendants of the progenitors of indigenous domestic caprines, are instead the feral descendants of Near Eastern caprines.” (Domestication and early agriculture in the Mediterranean Basin: Origins, diffusion, and impact; Melinda A. Zeder)

In other words, studies from a variety of disciplines, including genetics, have shown that most domesticated grains and domesticated animals – including those formerly though to have been independent wild herds – in fact trace their ancestry to a surprisingly small area in the Anatolian highlands, precisely where the Hebrews claimed the ancestors of all mankind (and, naturally, their herds and crops as well) initially dwelt after the flood.

What are the odds? This is not something that could have possibly been known in ‑500 by a small tribe of Jews in Babylon. By that time, no one on Earth could have known it, unless it was written in a more ancient text.

STONE TO IRON

To point out the elephant in the room, science places the domestication of sheep and the building of Gobekli Tepe at around ‑7,000-9,000. How do we feel justified in saying that supports our case, when we claim Noah was responsible for these things around the year ‑2300? I’m glad you asked.

These sorts of dates are derived from two sources; first, carbon-14 dating, which becomes more unreliable the farther back in history you go (and is built on flawed assumptions to begin with); still, we accept that generally, their dates do have meaning in a strictly relative sense.

Which is to say, something dated at 10,000 BC is probably older than something dated 8,000 BC; even if the true dates were in fact ‑2300 and ‑2000. Because, barring errors, carbon-14 probably generally provides useful data indicating the relative age of two objects.

The second way they arrive at these dates is their broad outline of history; things that fit a certain profile belong in a certain age. And historians had decided that civilization began 10,000-5,000 BC long before carbon dating came around. They did, in fact, calibrate the carbon dating to help match their assumptions.

And in this ascent-of-man theory, humans have been on a slow upward crawl, technologically. First we used wooden spears; then for tens of thousands of years used stone tools; then discovered copper (which for many purposes, wasn’t really better than stone).

Then after a thousand or two years passed they mixed tin with the copper to make bronze, then finally – after around two thousand more years – started using steel around 1200 BC. The presence or absence of these metals is strongly used to date settlements.

Simultaneously, the story goes, man was discovering that farming was more reliable than gathering, domesticating animals was better than hunting them, and so on. It’s a good story. It’s easy to package up and teach, which is why we all read it in our school textbooks… but it’s simply not true.

Most American Indians were living in the stone age just a few centuries ago; there are indigenous tribes in Papua New Guinea and Brazil and elsewhere who still do. And it goes the other way, too – sometimes ancient people had things they just shouldn’t have had in those times – that is, if the traditional story were correct.

We are told that iron wasn’t used until ‑1200 (‑800, my dating), except rarely when a meteorite was found (they’re almost pure iron, so didn’t need to be processed in a furnace). But iron made in a smelter (a specialized furnace) didn’t exist until the ‑1200s.

Yet we are immediately suspicious, because Moses wrote about iron frequently in approximately ‑1450 (Numbers 35:16, Deuteronomy 3:11, for instance). Nor was it meteoric iron, but explicitly smelted in a furnace (Deuteronomy 4:20).

Historians casually wave their hand and dismiss the Bible as myth. In fact, they use this as proof; since they are confident that iron was not smelted in ‑1450, it “obviously” means the Bible was written much later in Babylonian times (-600-500). Or else, you know, they are wrong.

But our policy is to believe all the evidence, especially written evidence; so imagine my surprise when, at a museum near the site of Ur, I found that there was iron being used in ancient Mesopotamia in 3,000 BC (their dating, not mine).

Nor are these particularly ceremonial objects; hairpins, arrowheads, spearheads, some sort of scraper. 2,000 years before the “iron age” in Mesopotamia! Furthermore, a very ancient hero of Mesopotamia, Lugalbanda whom you’ll meet soon, had an iron knife!

They pushed into place at his head his axe whose metal was tin, imported from the Zubi mountains. They wrapped up by his chest his dagger of iron imported from the Gig (Black) mountains. His eyes – irrigation ditches, because they are flooding with water – holy Lugalbanda kept open, directed towards this. The outer door of his lips – overflowing like holy Utu – he did not open to his brothers. When they lifted his neck, there was no breath there any longer. His brothers, his friends took counsel with one another: (Lugalbanda and the Mountain Cave)

That story, it is generally believed, was composed no later than 2,000 BC. So how did he have an iron dagger? So I looked deeper, and upon further research, I found that the entire narrative of the iron age is wrong and scientists know it, and don’t bother to tell you… because it’s such a nice story!

Early Iron Age artifacts found in Kültepe, in Azerbaijan, show that iron smelting was known and used in this region before the 2nd millennium BCE (as early as the 3rd millennium BCE)… in Mesopotamia, in Sumer, Akkad, and Assyria, the initial use of iron reaches far back, to perhaps 3000 BCE. One of the earliest smelted iron artifacts known was a dagger with an iron blade found in a Hattic tomb in Anatolia, dating from 2500 BCE… (Iron Age in western Iranian Plateau: a Long Debated Question; Genito, et al)

This is not meteoric iron, which has a unique alloy of nickel and is easily recognizable; this is explicitly smelted iron, over the entire cradle of civilization, as much as 2,000 years before we were taught that it existed!!

Why is that in none of the textbooks? That mankind had the knowledge of how to work iron 5,000 years ago, then somehow gradually lost it, then gained it back again only 3,000 years ago?

It just goes to show you… historians never let facts get in the way of a good story.

THE DATING CONTINUES

Because despite knowing this, when historians find an ancient campsite with a worked stone tool, they say “stone age!” and confidently date it 10,000 years ago. Another campsite nearby with a copper tool prompts them to say “copper! 5,000 years ago!”

But finding a stone arrowhead in a campsite doesn’t necessarily date that to 10,000 years ago; metal was expensive, especially early on in the post-flood world. People who couldn’t afford metal used what they had. Even side by side with cultures or individuals who had more advanced metals!

And it has nearly always been the case that people who dwell in cities are richer than those who dwell in tents or caves; which will automatically make cave-dwellers seem far more ancient than city dwellers if we date solely by the technology they possess.

Many supposedly “stone age” settlements were just poorer tribes making do outside the bounds of civilization without access to smelters and so on; not unlike how the stone age American Indians lived alongside the industrial age Europeans for most of the 19th century.

But that didn’t mean a person who used a flint knap, like Crazy Horse, necessarily lived 10,000 years before a guy who had a gun, like General Custer. He just, y’know, couldn’t afford one. The same goes for hand thrown vs. turned pottery, weaving, iron, and most of the other things used to date civilizations.

All of this is just to say that the 6,000 years or so of “prehistory” between the rise of civilization and the first writing can be reasonably compressed into just a few hundred years’ time between the flood and the time of Abraham.

Because the archaeological record does not show the tidy tale we’ve been taught. It shows that from the earliest days, mankind had a great deal of the technology that was later lost, then relearned, and sometimes lost again.

TWO PARADIGMS

Remember, anthropology is directly tied to evolution – the idea that man’s intellect was evolving upward from neanderthals as he dimly groped towards the ability to shape tools and preserve food, always improving. That theory, if correct, would allow us to date objects on an easy scale from simple to complex; the simpler they are, the more ancient.

The problem is, children today make pots that look not unlike those of the bronze age; are they, therefore, 5,000 years old? Thus finding less complex artifacts need not necessarily express age, but simply the skill, poverty, and haste of that individual or tribe.

We, on the other hand, believe man to have been intelligent from the day he was created; his brain did not need to evolve for him to learn to farm faster, to kill better, to build out of stone instead of sticks. Evolution takes eons; technology takes only a few generations, with highly motivated, intelligent people.

And after the flood, man was highly motivated to solve the problems of his environment. Yet, like castaways on a desert island, woefully backward in terms of resources, obsessed with survival.

Many technologies that existed before the flood would have necessarily been lost, just as you would be unable to make a cell phone as a castaway, or a cast-iron skillet, or even a cast. We’ve all seen Robinson Crusoe. And yet that doesn’t imply you lacked the understanding of these things, just the tools to make the tools to make the tools to make them.

Yet assuming that you were never rescued and somehow survived, your kids would only hear vague stories about magical talking devices, without the slightest idea of how they work. They would be able to learn only what is practical in their environment – not the operating principles of a blast furnace to make steel, with an ore not found on their island.

And so it was after the flood.

THE REAL NEOLITHIC

Genesis 4:22 Zillah also gave birth to Tubal Cain, the forger of every cutting instrument of brass and iron. Tubal Cain’s sister was Naamah.

Tubal-cain (not to be confused with Cain who killed Abel) was the last generation to be born before the flood, and he knew how to make brass and iron before Noah. But making iron requires a lot of steps, and it requires something not present in Mesopotamia at all… iron ore!

And since all of mankind was in Mesopotamia for several hundred years… naturally, they had almost no iron or copper! And by the time they did spread abroad across the Earth and discover metal deposits, exploit them and establish trade routes, the people who had survived the flood and had knowledge of how to work iron were likely dead or far away.

Hence, it looked like the ascent of man but really, it was just the gradual rediscovery of what had been lost. A literal post-apocalyptic scenario, minus the zombies (probably).

So it need not take 5,000 years for man to progress from flint to copper tools, nor two or three thousand years for him to decide that copper was better than stone. No, it only needed one smart dude and a copper outcropping.

Same goes for pottery eras; they didn’t need to last for a millennium before a guy decided to make different shaped scratches in his pot. Thus, the achingly slow climb of man need not take 10,000 years; a few generations would be enough. Therefore, the stone ages need not really last for ages.

Which means that when you read about the “neolithic” in the following chapters, the “new stone age,” it refers to the period shortly after the flood, precisely how archaeologists have dated the settlement at Gobekli Tepe.

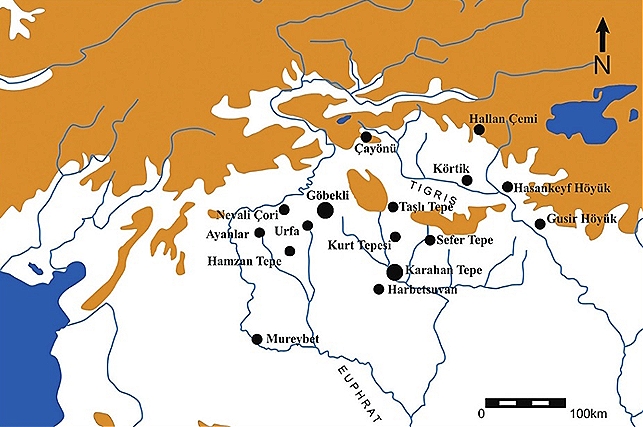

Gobekli Tepe is the largest of a group of ancient sites, spread across the headwaters of the Tigris-Euphrates system where farming was easy and game was plentiful in the early days of history. The region was wetter then, and massive herds of antelope and other game was common.

One of the earliest known sites is Körtik Tepe, dated to 10,700-9,250 BC, which may have been a predecessor of the PPN artistic and material culture in Upper Mesopotamia, including Göbekli Tepe and the other Taş Tepeler sites. (Ibid)

The site reached its peak in terms of occupation density around 9,300 BCE. Subsequently, it experienced an unexplained abandonment circa 9,250 BCE, possibly attributed to natural disturbances such as flooding induced by the warming of the Holocene climate changes. (Wiki, Kortik Tepe)

We actually can provide an explanation for that abandonment, as you will see in a moment, and it wasn’t climate change (always their go-to explanation for unexplained changes in civilizations). It was in fact overpopulation. But I’m getting ahead of the story.

BE FRUITFUL

The blessing of God ensured maximum fertility for Noah’s three sons – we presume Noah was done multiplying at this point – and therefore we should expect an average of three children to be born per year to the three sons.

That said, based on the genealogy in Genesis 10, we see that Shem had five sons, Ham had four, and Japeth had seven (consistent with his father’s blessing of “enlarging” him). Obviously, they also had daughters although there is no record of how many or their names.

It seems at first odd that so few sons were born, considering the long lifespan and the urgent need to repopulate the Earth; but if God really wanted to multiply humanity on the Earth as fast as possible, the blessing of “being fruitful” would require a lot more daughters than sons – there being no cultural taboo against polygamy at the time, this would be the fastest way to “replenish the Earth” (Genesis 9:1).

Thus it seems likely that Noah’s three sons had the aforementioned sons, along with a quite large number of daughters. Predicting the population growth is quite literally impossible without knowing how many females there were; but we can establish some absurdly low and high bounds to get some sense of it.

Starting from 16 male grandsons of Noah as adults at approximately ‑2284 (30 years after the flood), and assuming strict monogamy for low-end numbers, but with large families of 6-8 surviving children, ChatGPT gives anywhere 2,600 to 8,200 people alive after a century, in the year ‑2183.

If, however, we assume a skewed male-female birth and marriage ratio of 1-7, and that each woman had 6-8 children, the number jumps to anywhere between 100,000 and 300,000. This would not happen in normal circumstances, but God had blessed them saying “be fruitful,” and this is a perfectly reasonable way He might have done that.

These numbers are based on sheer guess work, and I have no intention of defending them. I merely wanted to see the types of numbers we would be dealing with after only 100 years from the flood. Most likely, something between 10,000 and 100,000 people would have been living around Gobekli Tepe by the year ‑2200, and something would have to give. But what?

THE SECOND MIGRATION

If we’re right, then Noah settled in the first of these cities, Kortik Tepe or thereabouts. From there, as his children multiplied, they built other settlements, finally culminating in the megalithic (big-stone) achievements of Gobekli Tepe, shortly before they abandoned the site after 100 or so (not 1,500) years.

It’s important to note that people who plant vineyards are not intending to travel much, thus, Noah intended to remain there indefinitely; he had done his work in saving mankind, it was up to his three sons – Shem, Ham, and Japheth – to obey God’s command to “Be fruitful and multiply. Increase abundantly in the earth, and multiply in it” (Genesis 9:7). However, this ran at odds with their own stated desire:

Genesis 11:4 They said, “Come, let’s build ourselves a city, and a tower whose top reaches to the sky, and let’s make ourselves a name, lest we be scattered abroad on the surface of the whole earth.”

It was explicitly this struggle of wills between Noah’s sons and God that led to the tower of Babel. So naturally, we would expect the first settlement of Noah to be surrounded by many more settlements “lest we be scattered abroad on the surface of the whole earth.” And that’s exactly what we find. This picture shows all of the “Neolithic” settlements related to the Kortik/Gobekli Tepe area.

It was explicitly this struggle of wills between Noah’s sons and God that led to the tower of Babel. So naturally, we would expect the first settlement of Noah to be surrounded by many more settlements “lest we be scattered abroad on the surface of the whole earth.” And that’s exactly what we find. This picture shows all of the “Neolithic” settlements related to the Kortik/Gobekli Tepe area.

Historically, people have often resisted that command to disperse; Jesus told the disciples to go into all the world and spread the gospel (Matthew 28:19) – an analogous command – and yet none of them seem to have really left Jerusalem for any length of time until they were forced to do so by the Roman conquest 40 years later.

Likewise, Noah’s sons explicitly resisted being scattered abroad until they, likewise, had no choice. The upper Euphrates could not support 100,000 people. The game would be exhausted; the land would not support the farming; the waste alone could create a major problem.

We begin to see, now, why Gobekli Tepe was abandoned so suddenly. And how the Bible can provide answers where historians have none, except vague gesturing towards “climate change.” It wasn’t climate change, it was overgrazing, overfarming, and overhunting caused by overpopulation.

So when it was increasingly hard to survive there, the first family had no choice; they had to move. And they wanted to stay together, as we are specifically told in Genesis 11.

So when it was increasingly hard to survive there, the first family had no choice; they had to move. And they wanted to stay together, as we are specifically told in Genesis 11.

But where? Certainly not north, for all the reasons they had they left it. Moving west would have required sea-faring boats, and it would have been very hard to move all of the people and their belongings that far by boat. No, the answer was obvious; build rafts and float down the Euphrates, looking for a better place to live.

What were they looking for? Specifically, a place that could support an enormous and fast-growing population, a place not bounded by natural barriers like mountains or oceans. And they found the perfect place in the plains of Shinar.

THE PLAINS OF SHINAR

What makes Gobekli Tepe so important to archaeologists is that they found massive stone structures, and buildings made with cut stone. Which is exactly what makes it important to us: because when the Bible tells the story of the first settlements in Mesopotamia, it tells us they already had experience building settlements made of stone before they arrived in Mesopotamia!

Genesis 11:3-4It happened, as they travelled east, that they found a plain in the land of Shinar, and they lived there. They said one to another, “Come, let’s make bricks, and burn them thoroughly.” They had brick for stone, and they used tar for mortar. They said, “Come, let’s build ourselves a city, and a tower whose top reaches to the sky, and let’s make ourselves a name, lest we be scattered abroad on the surface of the whole earth.”

Shinar is generally agreed to be central/southern Mesopotamia, near where Babel was built. Now the Bible seems to imply that this was the very first settlement after the flood, but when you think about it, it couldn’t have been.

There were clearly thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of people involved since the work of building a monumental tower could not have been done by eight people. That alone tells us that, for something like a century, they must have lived somewhere else in order to multiply to such an extent; therefore Babel cannot be the first settlement after the flood!

Furthermore, the fact that these people, none of whom had been alive before the flood, had experience working with cut stone… meant they had already done so at some post-flood settlement! Which means somewhere on this Earth, there should be cut stones made by the sons and grandsons of Noah before they arrived in Mesopotamia. Gobekli Tepe!

But in the broad plains of Mesopotamia you will not find a single rock for hundreds of miles in any direction. It’s just mud and dirt everywhere – which is awesome for food production, but requires extra effort to make into a building material. Something they had no experience with!

This is why they had to learn how to build out of brick and tar instead of rock and mortar.

EVIDENCE OF A NON-SUMERIAN ORIGIN

The focal point of later Mesopotamian religious worship was the ziggurat, or stepped pyramid, in the town center. It was the first of these which was called “the tower of Babel” in Genesis. To the Sumerians, these were meant to be artificial mountains. To quote one contemporary text explaining how the Sumerians themselves felt about their ziggurats…

In the city, the holy settlement of Enlil, in Nibru, the beloved shrine of father Great Mountain, he has made the dais of abundance, the E-kur, the shining temple, rise from the soil; he has made it grow on pure land as high as a towering mountain. Its prince, the Great Mountain, father Enlil, has taken his seat on the dais of the E-kur, the lofty shrine. No god can cause harm to the temple’s divine powers. Its holy hand-washing rites are everlasting like the earth. Its divine powers are the divine powers of the abzu: no one can look upon them. (Enlil in the E-kur)

This was for the dedication of the E-kur, literally “mountain house,” the ziggurat at the center of Nippur. Enlil was one of the greatest gods, occupying a place in Sumerian mythology similar to the Christian Logos or Word or Christ; Enlil was the son of Anu, mightier than all other gods but his Father (at least in most versions). And Enlil was called “father Great Mountain,” and lived in a ziggurat named the “mountain house” of Enlil.

There is a clear association of Ziggurats with mountain houses. Mountain houses play a certain role in Mesopotamian mythology and Assyro-Babylonian religion, associated with deities such as Anu, Enlil, Enki and Ninhursag. In the Hymn to Enlil, the Ekur is closely linked to Enlil whilst in Enlil and Ninlil it is the abode of the Annunaki, from where Enlil is banished. The fall of Ekur is described in the Lament for Ur. In mythology, the Ekur was the centre of the earth and location where heaven and earth were united. It is also known as Duranki and one of its structures is known as the Kiur (“great place”)… A hymn to Nanna illustrates the close relationship between temples, houses and mountains. “In your house on high, in your beloved house, I will come to live, O Nanna, up above in your cedar perfumed mountain.” (Wiki, Ekur)

But why place the gods in mountains which your average Sumerian had no contact with at all? It makes sense in say, Greece, where you can see the mountains more or less everywhere; high, awe-inspiring, mysterious.

But having been to Mesopotamia myself, it’s difficult to overstate how boring the landscape is. True mountains lie hundreds of miles away. So why build their universe around a mountain icon? Why not worship something closer at hand like the river or the grains? To be sure, they did – but those gods and forces were subjected to the God of the mountains.

If they really had lived in Sumer for five or ten thousand years, as historians mostly believe, why the obsession with mountains? There must have been a strong reason to think of a mountain as significant, holy, the abode of God. One which was worth the monumental effort (literally) it took to build artificial mountains in every city. Why would that be?

Because they had come from a mountain, and God had spoken to them at one.

Genesis 8:18-9:1 Noah went out, with his sons, his wife, and his sons’ wives with him. Every animal, every creeping thing, and every bird, whatever moves on the earth, after their families, went out of the ship. Noah built an altar to Yahweh… and offered burnt offerings on the altar. Yahweh smelled the pleasant aroma… God blessed Noah and his sons, and said to them, “Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth.

This would have been at the base of Ararat. At least eight people still living had been there. Their children all heard the stories. And note that “the Ekur was the centre of the earth and location where heaven and earth were united.”

Imagine, just as the ark landed on Ararat, a vast sea of nothingness; the entire human species on a small point of rock with ocean below and sky above. Wouldn’t be hard to think this site was the center of the Earth, the location where Heaven and Earth met, would it? And they never forgot that experience.

Now Ararat is quite a picturesque mountain, with a classic shape. Very regular, very conical. Just like ziggurats.

Sumerian legends are full of references to a holy mountain, where laws were given and God dwelt and so on. Why did the primitive Sumerian cultures so highly venerate mountains… unless they had, indeed, migrated from just such a mountain only a few generations before?

In fact, throughout the world there is a trend towards having pyramids in pairs. Mayan temples were often in pairs – arguably the majority of the time, in fact, we find them in pairs. Think of the temple of the sun and moon in Teotihuacan.

Do you notice a distinct resemblance? Meanwhile in Uruk we find it to be split from the earliest time into two neighborhoods, named as if they were cities even though they were only 500 meters apart; each built around a temple; one dedicated to An, king of the gods, and one dedicated to Inanna.

Meanwhile at Kish, the first city, to this day the remnants of two ziggurats – a larger and a smaller one – are still visible.

Why the need for two artificial mountains, one of which is clearly intended to be larger than the other? Take one more look at Ararat and you tell me.

DWELLING IN SHINAR

Having established that the human race migrated from Ararat to Sumer over the course of about 150 years, did they immediately go straight to rebellion and building the tower of Babel? Or was the settling process a bit more nuanced than that?

Genesis 11:1-4 It happened, as they travelled east, that they found a plain in the land of Shinar, and they lived there. They said one to another, “Come, let’s make bricks, and burn them thoroughly.” They had brick for stone, and they used tar for mortar. They said, “Come, let’s build ourselves a city, and a tower whose top reaches to the sky, and let’s make ourselves a name, lest we be scattered abroad on the surface of the whole earth.”

From the Bible, it seems that it all happened quite quickly, but remember the book of Genesis is a highly condensed narrative; it purports to tell 2,000 years of history in eleven short chapters, three of which are mostly genealogy.

That passage seems to imply that the tower of Babel was built immediately, but it doesn’t have to be read that way. Every time “they said” something, an interval of months or even decades might have intervened. So we also allow the possibility that it meant… “they found a plain and they lived there… [for a while, and then]… they said let’s make bricks… [and then they used them for normal buildings for a while]… and they said and build a city and a tower.”

Read this way, it would imply three distinct periods between their arrival and the tower of Babel; first, the arrival and early settlement in Shinar, probably in tents (Genesis 9:21); then the development of bricks for early house structures, forming villages; and finally the building of a proper city (Babel) capable of housing them all with a grand tower/ziggurat to represent the center of the universe (and also to provide flood insurance).

This is far more realistic than the implication we read into the Bible that “they landed in Shinar, discovered brick making and immediately set out making a massive, difficult structure the second they arrived.” Which means that most likely these three phases took decades, even a century, to happen.

Fortunately, we have another, contemporary source, which sheds a lot of light on what happened – and even how long it took! So now it’s time to introduce you to our second witness; the Sumerians themselves. Without both documents, you can’t really understand what went on in these early years.

This is part 3 of The History of the World Series