Most people don’t realize that there is actually an independent record of the earliest times in Sumer that parallels the Bible’s story in several main points. It talks about a global flood, for example, which only one man and his family survived via an early warning and the building of a boat.

Ancient Sumerian texts also mention the divine creation of multiple languages where before there was only one – analogous to the Biblical story of the tower of Babel. There are stories which echo Cain and Abel, Enoch’s ascension, and a place sounding much like the garden of Eden.

Historians tend to universally take these early Sumerian myths as inspirations of the Bible, thus negating any truth to be found in the Bible. In an article referencing the so-called Eridu Genesis, a creation story found in the city of Eridu, we find a representative quote:

The narrative of biblical Genesis shows some striking parallels… so that scientific research has long assumed prehistoric influences on the emergence of Mosaic religion. (Wiki, Eridu Genesis)

This assumption is difficult to believe. Why would the Mosaic religion, born in Egypt and bred in Canaan, be influenced by stories from Sumer in what was certainly a foreign tongue to Moses?

Remember, historians believe that Moses, if he existed at all, lived around the 13th century BC. How would he have become acquainted with these ancient Sumerian legends from what was, to him, the other side of the world? And written a millennium or two earlier besides?

And why use Sumerian legends at all, why not just use some handy Egyptian legends instead? Yet the book of Genesis shows far more similarities with ancient Sumerian myths than with contemporary (to him) Egyptian ones. Making it unarguable, even to historians, that one influenced the other.

The book of Genesis knows things about Mesopotamia that no person could have known who hadn’t been there. The fact that they built “towers,” for example; the names of cities like Babel, Erech (Uruk), Accad; the name of civilizations far outside Israel’s cultural horizon, such as Elam. These are facts which appear in Genesis which cannot be guesses; someone told Moses these things.

Yet historians can offer no plausible way that it was transmitted to Moses; but we can. In fact, the only way it’s even possible is if the information about Sumer was transmitted to Moses from Abraham who was from Sumer.

But that requires us to accept Abraham as a real, historical person; and that drifts dangerously close to accepting the Bible’s witness as the truth. But like it or not, it contains real historical truth about ancient Sumer. That must be explained.

Despite these very real problems with the theory, historians pretty much universally take the approach that somehow, someway, the Sumerian religion passed on its oldest traditions to the religion of Moses, who modified it to fit his own purposes.

We, on the other hand, consider the witnesses independent; Abraham was from there, told stories to his children who eventually told Moses. Giving him a credible, authoritative, but independent viewpoint, and arguably more objective viewpoint, on the same events as described by the Sumerian kings in their tablets.

These stories passed relatively (if not completely) unchanged down to Moses, whereas the Sumerians were actively updating and evolving them to suit the political and religious purposes of each city and king; by the time of Moses, the Sumerians only had vague superstitious memories of the flood and the events surrounding Babel.

Yet in these ancient Sumerian stories there is real truth, and the older the story, the closer to the truth it is. Which is why Moses’ stories echo the Sumerian ones – they were based on a shared experience between Moses’ ancestors and the ancient Sumerians.

VALUE IN MYTH

But if we believe, with Christians, that the Bible is the more authoritative and accurate version of these events, we disagree with Christians that the myths are utterly useless; however distorted they might be for political or religious gain, it is still possible to extract a lot of information that bears on the environment and experiences of the Bible.

Naturally, the older the myth, the more accurately it will tell the story; which is why it is the oldest ones which agree closest with the Bible’s story. Later Babylonian tales, like later Egyptian tales, bear only a passing resemblance to the Bible; this, again, tells us that if there was an influence on the Mosaic religion, it happened in the remote past, not in the time of Moses himself.

But the Bible was written and preserved with the specific aim of showing what happens when people defy the true God, and to explain why He chose certain people like Noah and Abraham to bless above the rest of the Earth.

So while the Bible is accurate, it was unfortunately not particularly concerned with the minutia of civilizations unless it impacted that message. It was content to gloss over details that didn’t pertain to its story with lines like “and they dwelt in Shinar; and they built a tower,” that may have taken centuries of real time.

Sumerians, on the other hand wrote extensively – but with a tendency to exaggerate the accomplishments of their king, or to glorify the gods they had imagined were behind what went on in their lives.

Yet so close in time were they to the events and people mentioned in the Bible that they can provide a great deal of information about the world in which they lived – and sometimes, even mention them directly. But only by taking these two sources and weaving them together does a story begin to appear that makes sense.

THE SUMERIAN KING LIST

One of the primary documents we will be referencing often for this early history is called the Sumerian King List (SKL). The SKL was compiled in antiquity between ‑2000 and ‑1500 (my dating), by author(s) who had access to the very ancient records of the earliest king lists stored in the cities of Sumer, especially those of Uruk, Kish, and Ur.

This unknown author was evidently commissioned by the king to compile a record of all those who came before him, not unlike Manetho was ordered to do by the Greek pharaoh Ptolemy. It was copied and updated several times in antiquity to include new kings over time.

There is every indication that the compiler of this list took his job seriously and was not prone to wild invention, although he did make some demonstrable mistakes; although perhaps “mistakes” is the wrong word; he was clearly commissioned with a purpose, and it seems he did it well.

His job was to make his king’s predecessors seem as venerable and ancient as possible; indeed, to make the role of king seem as divinely ordained and significant as possible, by giving the illusion that there was only ever one ruler over all the cities of Mesopotamia at any one time.

So rather than give a list first of the kings of Kish from the earliest time to his then-present, then doing the same for Uruk, Ur, and so on, he did something different; he presented them as if they were successive, one city ruling all of Sumer, then the gods appointing a different city’s king as their chosen ruler, then another, and so on.

We know that this is wrong, because Aga, last king of the first dynasty of Kish, was conquered by Gilgamesh, fifth king of the first dynasty of Uruk; this is attested in very ancient, probably contemporary, records. Yet the SKL would have us believe four generations separated these people. There are lots of other examples, but you get the idea.

So since everyone knew roughly whether a king was recent, ancient, or somewhere in between, the scribe carved up the this long list of kings into shorter chunks, and interspersed them with each other so that all the oldest were still the oldest, all the newest still the newest, even though they were presented as sequential to stretch out their length.

This led to us having what scholars call Kish I (the first 23 kings of Kish), then Uruk I (the first 12 kings of Uruk), followed by Ur I (the first four kings of Ur), then Awan I, three kings of Elam; followed by Kish II, Hamazi, Uruk II, and so on.

Breaking it up this way keeps the earliest kings in rough proximity to each other, even as they are incorrectly presented sequentially, making the history seem upwards of 40,000 years long; but in reality, these kings ruled their respective cities more or less side-by-side for hundreds of years, not tens of thousands.

The definitive work on this was done by noted Assyriologist Thorkild Jacobson in his seminal work “Sumerian King List”; he compared all versions available to him, used the comparisons to establish the correct original version, and his work is till respected today despite some new information having been dug up (literally) since then.

He was the first to prove that the SKL was deliberately rearranged as a continuous list of dynasties under the rule “one king over all of Sumer,” even though the original compiler well knew that was not the case.

He was also the first to make a plausible reconstruction of how the chronology of these kingdoms was actually laid out, demonstrating that all together they required only about 1,000 years from the earliest kings of Kish to the time of the famous Hammurabi, king of Babylon.

I place it closer to 900 years, but we will get into the details of the list much later, at the proper time. For now we will take Jacobson’s conclusion as a working hypothesis and move on with our story.

FOREIGN COUNTRIES

When we left them, Noah’s descendants were being fruitful and multiplying in the regions around Ararat and building the first post-flood towns of stone in eastern Turkey, and gradually overpopulating themselves and being forced farther afield.

Their stated goal to keep together and the fact that the land upstream was picked pretty clean suggests that the whole family packed up and moved together – probably excepting Noah himself, who was evidently not present for the Babel incident, so may have stayed behind.

The rest floated downstream to try their luck in the land of Shinar – meaning literally, “between the rivers,” which is incidentally the same meaning as the Greek word “Mesopotamia.” Arriving there, there the SKL tells us they built the city of Kish, the first city built after the flood.

This city must be what Genesis 11:2 meant when it says “they dwelt there,” for an unspecified time before the building of Babel. The Sumerians themselves confirm this:

After the Flood had wiped out (everything),

After the destruction of the lands had been achieved,

After mankind was made (to endure) forever,

After the seed of mankind had been saved,

After the black-headed people (the Sumerians) had of themselves been lifted high,

After An and Enlil had called man by name,

After ensi-ship (had been established)

But kingship…

Had not yet descended from heaven… (an ancient Sumerian tablet, as quoted in Reflections on the Mesopotamian Flood; Kramer)

There is some debate about the meaning of titles in the earliest Sumer, but generally it’s agreed that lugal meant king and that ensi was something less; perhaps governor, perhaps elder; Wiki says, among other things, “ensi was considered a representative of the city-state’s patron deity.”

This would be very consistent with the Hebrew position of Judge in the book of Judges. Regardless, this refers clearly to a time when there were leaders, but not kings, after arriving in Sumer. Then, just like in Israel, a king began to rule.

The SKL lists 12 “kings” of Uruk, then of the “thirteenth” king of Kish says “Etana, the shepherd, who ascended to heaven and consolidated all the foreign countries.” We also have a separate myth describing how Etana became the first king of Kish.

So why does the SKL mention these other twelve kings? Most scholars assume they were late additions for some unknown reason; but we can do better; because something odd here is that these aren’t really names at all, they’re literally just words meaning “dog,” “lamb,” “gate,” “scorpion,” etc.

But that’s quite strange; because according to both our Biblical history and Sumerian history, there literally were no other people in the world at this time!

So who then were these “foreign countries,” or “other nations,” that were “consolidated” into his rule at Kish? Remember, at this point in the story “the whole earth was of one language and of one speech. It happened, as they travelled east, that they found a plain in the land of Shinar, and they lived there.”

The context is clearly that the whole human population was moving together; and so if the WHOLE WORLD was living in the plains of Shinar… WHO were these nations that Etana united?? We could just discard this as a late addition, a simple fraud; or we could try to make it make sense.

Always trust the historical source at least enough to hear it out; who could these nations be, in context? For that matter, who were these first twelve kings, if they couldn’t unite these other nations? What’s strange is that these kings have odd names, they’re literally just words meaning “dog,” “lamb,” “gate,” “scorpion,” etc. Naturally, scholars dismiss this as a later addition, and skip straight to the person both the SKL itself and other Sumerian histories credit as the first king of Kish, Etana.

If no other people exist, and the SKL specifically says that Etana was the first to unite “the other nations,” the SKL must expect us to know who these nations are in context.

Why list twelve obviously abstract names, and then say “Etana became king over the nations” unless the twelve names WERE the names of the nations over whom he became king! Thus, these twelve kings were not kings at all, as scholars correctly deduced. But they were wrong to dismiss them as fabrications; for without them, the story of Etana makes no sense!

These “kings” whom he conquered were actually the symbols of the tribes by which the whole family of man was organized, twelve groups under the seventy elders of Genesis 10, who were consolidated into one kingdom under Etana!

THE KING OF KISH

Later legends record that Etana was made king by Inanna (the queen of heaven), but was unable to have a child; so skipping over some stuff, he helped an eagle, had some dreams, then was carried by the eagle to heaven, the abode of the gods, and was given “the plant of birth” to help him have a child.

Stripping the worst of the mythology from this, it might imply that Etana had journeyed back to wherever Noah was to seek a solution to his problems; perhaps his barrenness, or more likely the political situation at the time, whatever that was.

Since Noah never died (at least, he hadn’t yet), he seemed immortal and must have been more or less deified in the eyes of most people; thus his home would plausibly be “the assembly of the gods,” just as Gilgamesh viewed it centuries later when he made a pilgrimage there to find the secret of immortality from Utnapishtim, the Sumerian name for Noah:

‘Because I am afraid of death I will go as best I can to find Utnapishtim whom they call the Faraway, for he has entered the assembly of the gods.’ So Gilgamesh travelled over the wilderness, he wandered over the grasslands, a long journey, in search of Utnapishtim, whom the gods took after the deluge; and they set him to live in the land of Dilmun, in the garden of the sun; and to him alone of men they gave everlasting life. (The Epic of Gilgamesh)

We will discuss Noah’s location much more soon, for now this indicates that going to visit Noah to get answers was an accepted practice, albeit an increasingly rare one by the time of Gilgamesh. So Etana “ascending up to heaven,” to “the abode of the gods,” would plausibly be a visit to get Noah’s blessing for becoming king over his descendants.

Evidently, Etana felt he was given divine blessing to rule over Noah’s family and was able to persuade the heads of the twelve tribes of the same thing; and so the SKL records: “After the flood had swept over, and the kingship had descended from heaven, the kingship was in Kish.”

And to help confirm this story, we know one fact for certain; for literally thousands of years after this, the title of “king of Kish” was the most prestigious title you could bear in Sumer. No conqueror was satisfied until he had extracted tribute from Kish, for the kingship of Kish clearly contained some legitimizing quality.

The Gudean cylinder, 500 or so years later, referred to a new temple as “pure like Kesh and Aratta,” showing that these two places were the purest places on Earth. Much more about Aratta in the next chapter. Regardless, historians have no idea why Kish or Aratta would be “pure” above other cities, but we can easily explain it if Kish was the seat of the first divinely sanctioned government of the heirs of Noah.

No other king could ever be satisfied until he could say he had ruled over it because it was the only real seat of power – ceremonially, at least. It was something like Jerusalem is today; pointless of itself, but vital for the legitimacy it conveys. So likewise possession of Kish meant something, because it was the first true kingdom after the flood.

TWELVE TRIBES

The first twelve entries on the SKL tell us that before the first king ruled at Kish, humanity had organized themselves into twelve tribes – twelve groups of people each ruled over by an elder or “prince,” who BECAME the first city “lest they be scattered among the face of the Earth!”

I don’t want to call God unimaginative, but He does strongly favor patterns. So consider that Jesus called twelve disciples, made them apostles and sent them to spread the gospel in different places, to build their own foundations as Paul called it (Romans 15:20). He also had seventy disciples in a different place (Luke 10:1).

More to the point, Jacob had twelve sons, which became twelve tribes. Each of these tribes had a banner to identify them; we have no idea what might have been on them, but we can plausibly suggest that Judah was a lion and Ephraim was a bull (Genesis 49:9, Deuteronomy 33:17).

Numbers 2:2 “The children of Israel shall encamp every man by his own standard, with the banners of their fathers’ houses: at a distance from the Tent of Meeting shall they encamp around it.”

So the idea that Noah’s family was similarly organized into twelve tribes, each of whom identified themselves with a different banner of the house of their father, having an abstract symbol like a scorpion, dog, or gate on it is extremely consistent with how God’s people were organized throughout history.

Furthermore, Israel was also ruled over by 70 elders (Numbers 11:25); thus, it’s not surprising at all to find seventy elders, heads of the family of man, in Genesis 10; count up every individual grandson of Shem, Ham, and Japheth, and you’ll get a total of seventy individual nations – and these men were the heads of those nations.

Just as Israel was composed of twelve tribes, with the ancestors – and thus elders – of those tribes numbering 70 at the time they went down into Egypt (Genesis 46:26-27). Egypt, which was also a descent to a land built around a fertile river in the south, and which also led to widespread idolatry.

God has routinely discouraged kings over His people, grudgingly accepting them as a last resort (Luke 22:25-30), due to the inherent risks in letting one man’s moral failings corrupt or destroy an entire people.

Which is why, when these twelve tribes eventually left Egypt for the Promised Land, after passing over the Red Sea – a “flood” – at God’s direction, Moses again organized them into twelve tribes with seventy elders over them, which is how they remained until they demanded a king over them. Sounds familiar, right? You don’t even know the best part yet!

1 Samuel 8:19-22 Nevertheless the people refused to obey the voice of Samuel; and they said, Nay; but we will have a king over us; That we also may be like all the nations; and that our king may judge us, and go out before us, and fight our battles… And the LORD said to Samuel, Hearken unto their voice, and make them a king…

And what was the name of that king? I’m sure you know his name was Saul. But in one of the weirdest coincidences I’ve ever seen – if it really is a coincidence… the first king of Israel, the one who united the twelve nations of Israel into one kingdom… was the son of Kish (1 Samuel 9:1).

And Etana, the man who united the twelve banners of Noah into one kingdom, built the city of Kish. Coincidence? Probably, but still…

ETANA IN THE BIBLE

We would expect to find a person in such a position of authority to be one of the seventy elders in Genesis 10; it being unlikely that some young upstart could arrive in such a position of power so early in mankind’s history.

Therefore, one of the names in Genesis 10 should be the Hebrew translation of Etana. Some historians derive the name of Etana from the mythology attached to his name, that he “ascended to heaven,” in Sumerian, literally Ed-Anna. Thus Etana or Edana might be acceptable variants of his name.

We should further be able to narrow down the list in Genesis 10 by considering that Etana built the city of Kish; and that most people name cities either after themselves, or their ancestor (Judges 18:29, for instance).

Now since Hebrew doesn’t record vowels and the letters C and K have the same sound in most languages, Kishis literally the same as the name Cush. Thus, we should expect Etana to be either Cush himself, or a descendant.

Cush was a son of Ham, and alongside his better known son Nimrod, his children are listed in Genesis 10:7-8; and his grandson is said to be named Dedan! Looking at the commentaries, it may have been meant to be pronounced Dedana in Hebrew.

Thus, Etana/Edana in Sumerian, first king of Kish and therefore descendant of Kish is almost certainly Dedana, grandson of Cush – who built the first city and named it after his grandfather!

THE SECOND CITY

So the children of Noah came to Shinar first as twelve self-governing tribes under the 70 elders of Genesis 10. Which is where Genesis 11:2 tells us, “they lived there.” Then later, they said “Go to, let us make brick, and burn them thoroughly,” they built Kish, and became the first city-state under Etana, approximately ‑2200; some time later, Nimrod came along…

Genesis 10:8-10 And Cush begat Nimrod: he began to be a mighty one in the earth. He was a mighty hunter before the LORD: wherefore it is said, Even as Nimrod the mighty hunter before the LORD. And the beginning of his kingdom was Babel, and Erech, and Accad, and Calneh, in the land of Shinar.

And this is where it gets really interesting, as we fold the Bible’s story in with the history of Sumer as told by the Sumerians; because according to the SKL, there was no such person as Nimrod. And of course, there wouldn’t be, because this is a story written in Hebrew, probably passed down orally from Abraham to his children centuries after the fact.

So I’m quite certain that if you had gone to the tower of Babel and yelled out “Hey, Nimrod!” no one’s head would turn even if that was a close variant of his name, it’s surely mangled in pronunciation by now. However, thanks to the magic of cooperation between the Bible and the SKL, we can pinpoint exactly who Nimrod was in the SKL!

Because reading Genesis, we see that Nimrod’s kingdom began at “Babel, and Erech…” Now Erech is just a different spelling of Uruk, just as the modern state of Iraq is a different spelling of Uruk. Thus, we see that Nimrod’s kingdom began at Babel and then he built Uruk later.

But that’s interesting, because according to the SKL there was no kingdom of Babel! No “first dynasty of Babel” is known from history until the time of Hammurabi, nearly a thousand years later. This is another reason why historians dismiss the Bible, but they shouldn’t – for the Bible explains exactly why this discrepancy exists:

Genesis 11:4-9 They said, “Come, let’s build ourselves a city, and a tower whose top reaches to the sky,… [God confused the languages, and then…] Yahweh scattered them abroad from there on the surface of all the earth. They stopped building the city. Therefore its name was called Babel, because there Yahweh confused the language of all the earth. From there, Yahweh scattered them abroad on the surface of all the earth.

This is why there is no city of Babel recorded in the early SKL; because they STOPPED BUILDING IT! And yet Nimrod’s empire began there. Because they STARTED building it. Thus the Bible is absolutely true, that his kingdom began at Babel.

But when God destroyed Babel, Nimrod moved on and built Uruk. Which is why the SKL is absolutely correct that there was no first dynasty of Babel because no one ever ruled at Babel!

Now if this site of Babel is at or near the site called Babylon under Hammurabi and Nebuchadnezzar – which is likely, but not certain – then it’s only about 12 miles apart; very close to Kish, and a severe threat to it – ideologically, if not militaristically.

But after God confused the languages and cursed the city, Nimrod moved to Uruk, 110 miles downstream… And there they built a city, and began recording the reigns of the kings of Uruk. Not at Babel, which never had a king.

What’s interesting is how accurate the Bible’s version is proven to be by science; because according to the Bible, the existence of Kish is implied; Babel was a failed attempt at city-building; the first city after that was Uruk.

And so we are, as always, impressed by the Bible’s knowledge of the earliest times in Sumer, for it says the first successful city was Uruk, built by Nimrod; and historians know that Uruk was the birthplace of writing, and was arguably the first city in the world.

Proto-cuneiform obviously reflects this context rich in creativity, and the fact that it is primarily documented in Uruk, the main settlement of the period (often labelled “the first city”), is no coincidence. (Wiki, Uruk)

How did some slaves in Egypt manage to guess this when writing Genesis? How had they even heard of Uruk?

THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL RECORD

The Bible isn’t clear what happened to make them stop the construction at Babel besides the language thing, but it’s likely some damage was done to the tower as well. Josephus says…

The Sibyl also makes mention of this tower, and of the confusion of the language, when she says thus: “When all men were of one language, some of them built a high tower, as if they would thereby ascend up to heaven, but the gods sent storms of wind and overthrew the tower, and gave every one his peculiar language; and for this reason it was that the city was called Babylon.” (Josephus)

Since wind couldn’t possibly damage a ziggurat, it must have done so with water. Either a massive flood from upstream – which is generally caused by rain in the mountains, not an actual storm in Sumer – or far more likely a tidal wave upstream from the Persian Gulf caused by storms in the Gulf. Note the parallels with how God used wind at the Red Sea.

Remember, the tower was specifically built to survive a flood. So if there were a flood capable of destabilizing an immense ziggurat, there should be an unmistakable sign of it in the archaeological record. And there is!

Some modern scholars… believe the Sumerian deluge story corresponds to localized river flooding at Shuruppak (modern Tell Fara, Iraq) and various other cities as far north as Kish, as revealed by a layer of riverine sediments, radiocarbon dated to c. 2900 BCE, which interrupt the continuity of settlement. Polychrome pottery from the Jemdet Nasr period (c. 3000–2900 BCE) was discovered immediately below this Shuruppak flood stratum. (Wiki, Eridu Genesis)

Mesopotamia, like other early sites of riverine civilisation, was flood-prone; and for those experiencing valley-wide inundations, flooding could destroy the whole of their known world. According to the report of the 1930s excavation at Shuruppak (modern Tell Fara, Iraq), the Jemdet Nasr and Early Dynastic layers at the site were separated by a 60-cm yellow layer of alluvial sand and clay, indicating a flood, like that created by river avulsion, a process common in the Tigris–Euphrates river system. (Wiki, Flood Myth)

Avulsion means the river flowed backwards from the sea; consistent with the “winds” that overthrew the tower. The fact that the civilization which rebuilt these settlements is distinct from that which came before (Jemdet Nasr) argues that this was indeed the catastrophe which destroyed Babel. It does not seem that God was content to just change the languages.

Historians mostly think this flood layer is that which is recorded in the Bible as the flood of Noah; preferring to believe that Sumer and the Bible grossly exaggerated a local flood – despite the fact that the entire world is full of global flood legends.

This is another example of how we need not fear science; but how scientific facts when correctly interpreted confirm the Bible’s story. This flood is not the flood, the one of Noah; it is simply a record of God flexing; saying the Titanic is so safe “God himself can’t sink it” is a gutsy move.

So is building a tower that reaches to heaven so that God Himself can’t drown you.

THE HISTORICAL NIMROD

And now we return to the SKL; the first king of Uruk, according to most scholars, is En-mer-kar. According to other Sumerian sources, this is the king who built Uruk; and if the Bible and the SKL are to agree, this must be Nimrod, the mighty hunter before the Lord.

But the name Enmerkar certainly doesn’t look like a match at first… until you learn that kar is the Sumerian word for hunter! Thus, this could be read as Enmer the hunter!

This is very exciting, but we can do more. Remember, Hebrew has no vowels. So if you wrote eNMeR-kar in Hebrew, you would, of necessity, write it as NMR the hunter! Which is certainly very promising, but still, NMR is not NMRD.

However, there is a curious fact about Sumerian writing; they often don’t write down “amissable consonants.” According to Google’s AI answer:

“An amissable consonant is a final consonant in a word that can be omitted in writing. This was common in the Sumerian language, where consonants like /d/, /g/, /k/, and /ř/ were often left out, especially at the end of a word.”

Note that “D” is one of the amissable consonants! Thus, a name that was pronounced with a D on the end may, in Sumerian, have been spelled without the D! But it was not omitted in Hebrew, which retained the correct consonants of the name NIMROD the MIGHTY HUNTER, Enmer-d-Kar!

Hebrew lost the vowels, since they only write the consonants. Thus, if you wanted to say “Nimrod” and have him actually recognize his own name, you would use the Hebrew consonants, guided by the Sumerian vowels; and you’d probably find that Nimrod pronounced his own name En-mer-ad, or some such.

To the Hebrews, this name came to signify rebellion, indicating that Abraham heard the story from ancestors who considered Nimrod to be the bad guy, which Moses faithfully (and accurately) passed on in Genesis. But in Sumerian, it had a different meaning…

“while the etymology stills unclear, “the ‘Lord’ (is / has) a glowing giant snake” has been proposed.” (Wikipedia, Enmerkar)

Thus, enmerkar (probably) means “the Lord (of Nimrod) is a glowing giant snake.” Name a kid that, and you can’t be surprised he turns out to be a deceiver of mankind, founder of the false religion that has deceived people since the time of Babel by pointing them towards the worship of the first deceiver of mankind – the serpent in the garden of Eden!

MUGSHOT

The best part of all of this is that we not only know Nimrod’s Sumerian name, we actually have his picture. Because history abounds with statutes and carvings of a mysterious figure – well, mysterious to historians – known as the priest-king of Uruk. Wikipedia summarizes:

The most prominent figure in the Uruk iconography is the so-called “Priest-King” or “Ruler-Priest,” an archetypal figure wearing a brimmed cap and a long kilt, with his hair bound up into a bun, …He is mostly found in the Uruk documentation, also in Susa, and even in Egypt on the Gebel el-Arak knife. On the ‘Uruk Vase,’ he leads a procession and offering towards the goddess Inanna; on the ‘Stele of the Hunt,’ he defeats lions with his bow. In other cases, he is shown feeding animals, which suggests the king as a shepherd who gathers his people, protects them, and looks after their needs, ensuring the prosperity of the kingdom. These motifs match the functions of the subsequent Sumerian kings: war-leader, chief priest, and builder. In the administrative texts, this ruler may be the person designated by the title of EN…. (Wiki, Uruk Expansion)

The first builder, warrior, and chief priest of Uruk was Enmerkar/Nimrod, as we have already seen many times. And this “most prominent figure” in Uruk can only be the very same person.

All of the pictures above are generally agreed to be depictions of the earliest priest-king of Uruk; notice the rounded beard (specifically forbidden in the Bible, Leviticus 19:27), and the rounded fabric headgear with a prominent band. This was a simple shepherd’s hat, not a crown – which would be the basis for standard headgear throughout Sumerian times.

… I would further suggest that the shepherd, which is clearly the model for Sumerian kings, was originally the model for a priest. Like a true shepherd, the priest gathers his flock (the people) at the temple and he administers to their needs, which is why a priest is often referred to as a shepherd in many religions of the world. The shepherd priest of Uruk would later become a shepherd priest-king, who then became the shepherd king — the ideal Sumerian king and the prototype for all other Sumerian kings. (Ibid)

I concur with this author’s conclusions; the role of shepherd, elder, and so on are certainly embraced by Jesus, and therefore would certainly have been used by Noah and his sons. It was the shift from shepherd-priest to priest-king that angered God – well, that and the devotion to the queen of heaven. Still, the Bible never complains about his idolatry directly, it focuses on his sin as “being a mighty hunter before the Lord.”

But what’s really interesting is how widespread this kings’ imagery is. In fact, the picture above at right is of a ceremonial dagger found in predynastic Egypt; meaning that Nimrod’s reach was as far as the Nile valley.

Precisely as the Bible would suggest it was.

THE DIVISION OF LANGUAGE

Interestingly, if Etana is the Bible’s Dedan, Nimrod would be his uncle. Apparently megalomania and world domination run in the family. And in case you still had any doubts that Nimrod is Enmerkar, we are about to put them to rest.

Fortunately there are preserved for us very ancient stories about this same Enmerkar, and his various exploits. The first is called “Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta.” Though written later, probably around ‑1600, it dates itself to the earliest days after the flood:

“In those days of yore, when the destinies were determined, the great princes allowed Unug [Uruk] Kulaba’s E-ana [temple] to lift its head high. Plenty, and carp floods and the rain which brings forth dappled barley were then increased in Unug Kulaba.”

Most interpret “great princes” as the Anunnaki, what we might call archangels; but another interpretation, consistent with the Bible, is that these “great princes” were the seventy elders who ruled over the twelve tribes of Noah; which would mean that these “great princes” allowed Enmerkar to build a city and become powerful.

In Uruk they built a temple to Inanna, the queen of heaven, in this story Inanna was displeased with Aratta (because they are not idolatrous enough) and therefore favors Uruk, who then demands recognition and tribute from Aratta, who refuses. What is most interesting for right now is the following passage…

“…At such a time, may the lands of [suffice it to say, a lot of places…]… the whole universe, the well-guarded people – may they all address Enlil together in a single language [again]! For at that time, for the ambitious lords, for the ambitious princes, for the ambitious kings – Enki, the lord of abundance and of steadfast decisions, the wise and knowing lord of the Land, the expert of the gods, chosen for wisdom, the lord of Eridug, shall change the speech in their mouths, as many as he had placed there, and so the speech of mankind is truly one.”

The first take-away from this passage is that Enmerkar is still trying to reverse the curse of the languages! Which means the frustration it caused his kingdom is still so recent, he is actively trying to fix it! This confirms the story in the Bible of the linguistic division, and does so in the context of Nimrod, and therefore Babel!

THE BIRTH OF WRITING

The story continues with various challenges between Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta, but soon a problem develops; all of this time, Enmerkar has been sending messages containing challenges back and forth via a messenger, and after the third (lengthy) message the messenger is supposed to take to Aratta…

…His [Enmerkar’s] speech was substantial, and its contents extensive. The messenger, whose mouth was heavy, was not able to repeat it. Because the messenger, whose mouth was tired, was not able to repeat it, the lord of Kulaba [Enmerkar] patted some clay and wrote the message as if on a tablet. Formerly, the writing of messages on clay was not established. Now, under that sun and on that day, it was indeed so. The lord of Kulaba inscribed the message like a tablet. It was just like that. The messenger was like a bird, flapping its wings;… He stepped joyfully into the courtyard of Aratta, he made known the authority of his king. Openly he spoke out the words in his heart. The messenger transmitted the message to the lord of Aratta:… “This is what my master has spoken, this is what he has said… Enmerkar, the son of Utu, has given me a clay tablet. O lord of Aratta, after you have examined the clay tablet, after you have learned the content of the message, say whatever you will say to me… After he had spoken thus to him, the lord of Aratta received his kiln-fired tablet from the messenger. The lord of Aratta looked at the tablet. The transmitted message was just nails, and his brow expressed anger. The lord of Aratta looked at his kiln-fired tablet. [whereupon a great storm happened, a bad omen; it isn’t clear how the story ends].

Note that the messenger presented a tablet, which was “just nails,” i.e., just appeared to be indentations of nails, as cuneiform tends to appear; after all, Nimrod had just invented writing, it is obvious that the Lord of Aratta hadn’t yet learned how to read!

Because to carry a message, it is not necessary that your audience can read; remember, the messenger complained of forgetting things – so writing was to help him remember, but he was still to announce the message in his own words.

Thus the earliest writing used stylized pictures, just enough to jog someone’s memory – just as, to this day, speech-givers write notes on cards, but use their own words when they speak. So writing down a picture of five bushels of wheat will remind him you wanted five, not four, and wheat, not wine. But it’s up to the messenger to fluff it up and phrase it nicely.

Which is why the simplistic nature of the earliest language isn’t so much language, per se, as it is reminders for the messenger who accompanied the message, and later as a reminder of the contract that was made or the offering given.

For the basics of communication, you really just need a list of noun-pictures and a few verbs that can be represented as pictures, like walking, eating, warring, etc. The next step is to learn how to use these pictures to convey things that you can’t easily draw – like “want,” and “hate,” or “Nathaniel.”

How all of these systems solved this problem was to use the pictographs for multiple purposes; a picture of a cat, for example, could mean the object “cat” or the sound for “cat” as part of another word. Add a picture of a golf tee, and you have the word “catty.”

This is broadly how the most ancient cultures conveyed information that wasn’t easily drawn as a pictograph, especially foreign names; and it’s the basis of how traditional Chinese conveys things that are not recognized symbols to this day.

COMMON ORIGIN

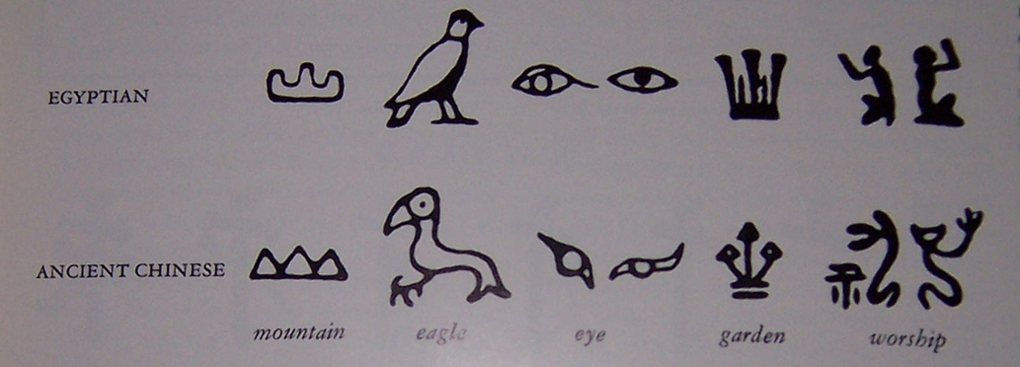

Not only did they solve the problems of writing in a similar way, but in all three of the earliest cultures – Sumer, China, and Egypt – the earliest writing bears a striking similarity to each other (the following picture from Readers Digest History of China).

There are cultures which, according to standard histories, had absolutely no contact. How, then did they come to make such similar signs? Sure, anyone would probably draw an eye to represent an eye; but would they draw a garden with three plants in it? A mountain with three peaks, just as the Sumerians do? Worshipers facing away from each other, not towards an altar which would be more intuitive?

These are coincidences which are hard to explain without some form of contact; unlike traditional historians, we are easily able to explain that contact: writing was developed in Sumer, as mankind was spreading out around the world, specifically from Sumer!

Genesis 11:7-8 “Come, let’s go down, and there confuse their language, that they may not understand one another’s speech.” So Yahweh scattered them abroad from there on the surface of all the earth. They stopped building the city.

Science supports this concept, even though scientists don’t like it, because there is a curious fact about written language; for it to have been invented at all, it must have gone through a stage of evolution; from scratches to pictures to words, that sort of thing.

And we can, in fact, trace the development of Sumerian cuneiform back to the most basic writing system, consisting of ledger entries. Basically, mankind invented excel spreadsheets first, and language later.

But what’s even more interesting is that we cannot do this with Egyptian hieroglyphs, which do not have a proto-writing! Nor can we do it with Chinese; there are simple pictures drawn on pots and such – art, not language – and then suddenly language, fully formed – and suspiciously similar to cuneiform.

But in Sumer, we can see all the steps of creating a writing system, from ledger entries to proper writing. Why do we only find proto-writing for cuneiform? Because that’s where everyone learned the concept!

Historians universally believe that these three writing systems developed independently; they are forced into this belief because they believe these cultures migrated to their respective locations tens of thousands of years ago while still in their naked-savage stage.

The idea of contact between them of any kind in 3,000 BC is unthinkable, impossible. It flies in the face of everything they believe, for it would mean that his technological abilities were not gained in one long slow climb as he slowly migrated around the world over eons.

Which backs them into a corner, despite a complete lack of evidence for proto-Egyptian and proto-Chinese, they have no choice but to believe that these three very similar pictographic scripts developed independently at roughly the same time in history.

They are not “following the science,” because the science clearly tells them that only one of these languages exists in its proto form, and that means that only one of them was developed; the other two were borrowed.

Not only that, but we have written evidence of the transmission of writing from Uruk to Aratta, a country to the east. We literally have ancient Sumerian records telling us that writing spread from Sumer to the world.

Exactly like the Bible says everything did.

THE URUK EXPANSION

As I said, science confirms that mankind was dispersed throughout the Earth from Babel; even if it would rather not talk about it. Remember, Babel was never finished, according to the Bible; so the people who built it moved on and dwelt in Uruk instead. So it was the culture we find at Uruk which would be that which we expect to find in those people who were dispersed from there. And what does science say?

Our only clues about the history of Iran during the 4th millennium BC are provided by archaeological data, in particular, the evidence of the “Uruk Expansion.” This immensely interesting historical and cultural phenomenon, which can roughly be dated to ca. 3500–3100 BC, involved a migration of significant numbers of people from southern Babylonia into its periphery. These individuals subsequently established a network of colonies, which, as far as it can be ascertained, functioned mainly, but certainly not exclusively, as trading outposts. (The Birth of Elam; Steinkeller)

Uruk expansion, dispersion from the aftermath of Babel; to-may-toe, to-mah-toe. We are as always impressed at how science – although late to the party – confirms the story of mankind spreading out from the aftermath of Babel; even confirming the exact city we would expect, from the Bible, for it to have spread out from.

The Uruk period is characterized by a phenomenon of “Urukean Expansion,” which is evident on the sites through the spread of the material and cultural traits typical of this culture, an Urukean “kit” including, in its final development, beveled-rim bowls, numerous forms of Urukean-type wheel-made ceramics, administrative and accounting tools (cylinder seals and bullae seals and numeral tablets)… Most sites are located along trade routes, especially in river valleys. The beveled rim bowls characteristic of the Uruk repertoire are found from the Caucasus to Pakistan. (Wiki, Uruk Period)

Scientists debate the causes, with the usual suspects being trotted out; but one of their theories, as it happens, is precisely the truth:

Since the identification of possible enclaves or settlements of Uruk culture, scholars have debated the nature of the phenomenon and its explanations… Other explanations propose a form of agrarian colonization following a lack of land in Lower Mesopotamia, or a migration of refugees from the Uruk region following ecological or political problems. (Wiki, Uruk Period)

A massive flood from the Persian Gulf that wiped out all the settlements and toppled the tower of Babel would certainly qualify as an “ecological problem.”

Genesis 11:8-9 So Yahweh scattered them abroad from there on the surface of all the earth. They stopped building the city. Therefore its name was called Babel, because there Yahweh confused the language of all the earth. From there, Yahweh scattered them abroad on the surface of all the earth.

And there is a linguistic element to this expansion as well; as the following author explains…

Because of their proximity to Babylonia, and of their being, in geomorphological terms, an extension the Babylonian floodplain, the regions that had been particularly strongly impacted by the “Uruk Expansion” were the Khuzestan and Deh Luran plains [SW Iran], to the extent that their material culture, represented at such sites as Susa and Choga Mish, is virtually indistinguishable from that found in contemporary southern Babylonia.

A likely reflection of this early Babylonian presence in Khuzestan is the fact that the name of the chief deity of Susa, Inshushinak, almost certainly derives from that of the goddess Inana, the patron of Uruk and the most important deity of Late Uruk times. Since the ultimate source of the “Uruk Expansion” unquestionably was the city of Uruk, it logically was during that particular time that Inana’s cult had been carried from Uruk to Susa (The birth of Elam; Steinkeller)

At the time of the Uruk expansion, the languages were in the process of changing, or had just changed; because the Elamites to the east, though they had just come from Uruk, and were worshipping the same goddess, culturally identical, yet somehow changed the name of their goddess from Inanna to Inshushinak, because that was what happens when God confuses your languages!

How else would recent migrants from a single homogenous Uruk culture, who certainly would have also had a single language, wind up speaking different languages immediately upon their arrival in their new home?

Think about that.