Enmerkar and Aratta

This is part 7 of the The History of the World Series

; Introduction is part 1.

Click here to read in series

One of the many mysteries about ancient Sumer is the identity of their mortal enemy known “Aratta.” It is mentioned frequently in Sumerian texts, where it appears as a holy place, a trading partner, a military adversary, and many other things.

Knowing the real answer of who it was will flesh out the story of the Bible, and doing that will allow us to answer many great mysteries about the ancient world that historians cannot answer. Because not only can we identify them, they are one of the most important peoples in the ancient world – all the more so, since no one knows them.

We know they were not located in Sumer, or anywhere in Mesopotamia. What’s so important for our purposes is the respect with which they were held; so let’s review some mentions of Aratta in various Sumerian texts, as cited in Wikipedia “Aratta:”

Praise Poem of Shulgi (Shulgi Y): “I filled it with treasures like those of holy Aratta.”

Shulgi and Ninlil’s barge: “Aratta, full-laden with treasures”

Proverbs: “When the authorities are wise, and the poor are loyal, it is the effect of the blessing of Aratta.”

The building of Ninngirsu’s temple (Gudea cylinder): “pure like Kesh and Aratta”

Tigi to Suen (Nanna I): “the shrine of my heart which I (Nanna) have founded in joy like Aratta”

Inana and Ibeh: “the inaccessible mountain range Aratta”

Gilgamesh and Huwawa (Version B): “they know the way even to Aratta”

Temple Hymns: Aratta is “respected”

The Kesh Temple Hymn: Aratta is “important”

Lament for Ur: Aratta is “weighty (counsel)”

Taking these together, we see that Aratta is “pure,” “respected,” “important,” and “weighty”; it was held a unique place of esteem in Sumer, so that good times are deemed to be the “effect of the blessing of Aratta.” In fact, the word “Aratta” is sometimes used as an adjective, as it was in the Kish temple hymn above, to mean “important, exalted, splendid, precious,” i.e., to say something was worthy of Aratta.

Its esteem is placed on par with Kish, if not greater than it. Since Kish was associated with kingly legitimacy for over a thousand years after its founding, Aratta must be even more so. How could that be? Well, if Kish was where kingship first started in Sumer… then Aratta must be where the men lived who gave even Kish its legitimacy. In one story, Aratta responds disdainfully to Enmerkar, saying…

Tell your King that the God of all heavenly laws has sent me to Aratta, the land of heavenly laws, to reinforce the gates of the mountains. (Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta, Majedzadeh 2019)

Combining that with our knowledge of the Bible, we can draw only one conclusion; that the rightful leaders of the human race dwelt in Aratta. Which is to say, the elders of the elders; which is to say… Noah, Shem, and Arphaxad.

BUT WHERE IS IT?

According to those citations we saw above, it was clearly far away, in a location not known to all in later times; in an “inaccessible mountain range”; but although it took on Shangri-la-like dimensions, it was beyond a doubt a real place because we have directions to find it!

The messenger [of Uruk] gave heed to the words of his king [Enmerkar]. He journeyed by the starry night, and by day he travelled with Utu of heaven. Where and to whom will he carry the important message of Inana with its stinging tone? He brought it up into the Zubi mountains, he descended with it from the Zubi mountains. Susa and the land of Anšan humbly saluted Inana like tiny mice. In the great mountain ranges, the teeming multitudes grovelled in the dust for her. He traversed five mountains, six mountains, seven mountains. He lifted his eyes as he approached Aratta. He stepped joyfully into the courtyard of Aratta, he made known the authority of his king. (Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta, ELA henceforth)

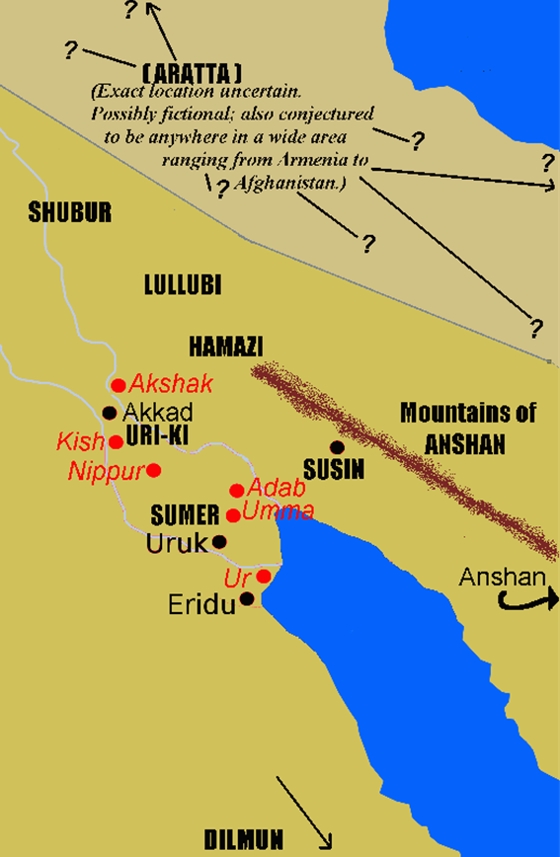

Using these clues, finding where and who Aratta was is very easy – but only if you actually trust these clues, which unfortunately historians won’t do. Their beliefs make them blind to the obvious conclusion staring them in the face; consider this map from Wikipedia, which says “Aratta; possibly fictional; also conjectured to be anywhere in a wide area ranging from Armenia to Afghanistan.”

Using these clues, finding where and who Aratta was is very easy – but only if you actually trust these clues, which unfortunately historians won’t do. Their beliefs make them blind to the obvious conclusion staring them in the face; consider this map from Wikipedia, which says “Aratta; possibly fictional; also conjectured to be anywhere in a wide area ranging from Armenia to Afghanistan.”

It’s absurd that there are so many theories, because the main place that talks about it all points to the exact same direction: due east. Not north, not northeast; because you certainly don’t need to go through Anshan (southeast) to get to Armenia (north)!

Enmerkar’s messenger shows us that to get to Aratta you must go up into the Zubi mountains (probably the Zagros), descend, go through Susa and Anshan, and then you find yourself “in the great mountain ranges,” then you must still traverse “five, six, seven” mountain ranges until finally arriving in Aratta. So when we actually follow the clues we have, we learn that the route to Aratta lies due east, across seven mountain ranges; if we put that on a map and try to follow the instructions we have, it would take us… to Pakistan.

Starting at Uruk and going to Susa and Anshan is clearly heading east; after that we find, right on schedule, a very rugged highland area – “the great mountain ranges”; followed by several more mountain ranges – “five, six, seven,” – culminating in the Sulaiman mountains, one of the chains that forms the SW part of the Himalaya system.

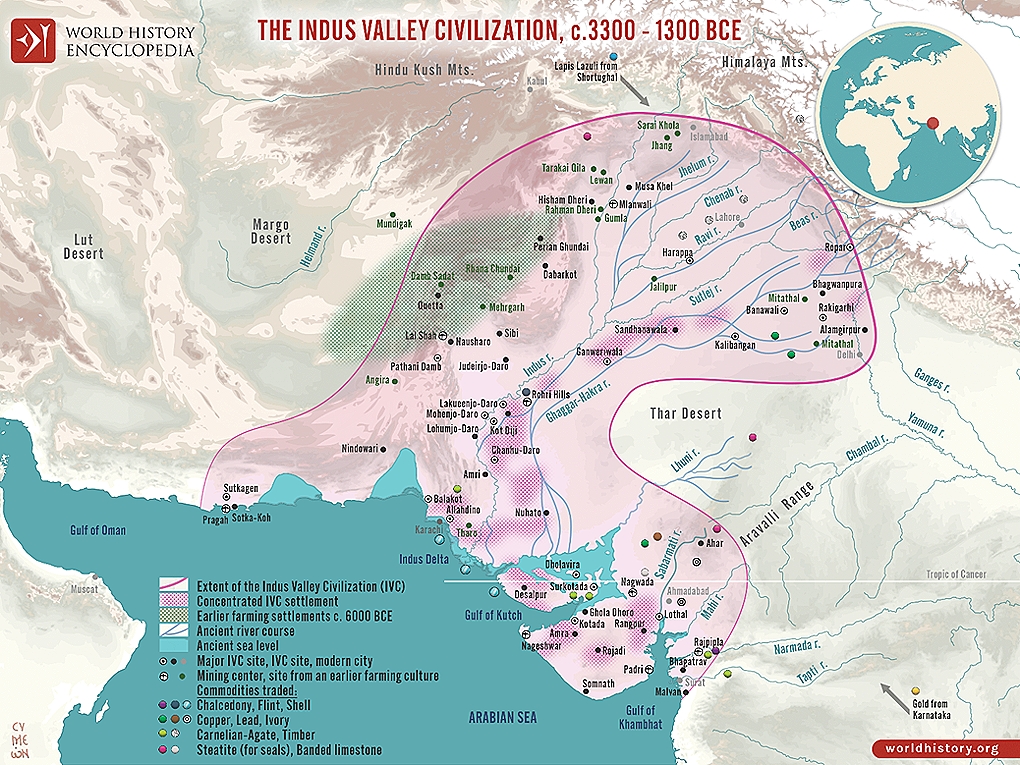

Note that this is not wishful thinking, this is simply following the precise directions given on the tablet. Heading east through these waypoints suggests you’re going to continue east; crossing seven mountain ranges is what would necessarily happen if you did that; as you can see from this topographical map, it’s not clear how to count them, but there are a lot of mountains to cross.

The only logical destination beyond them for a great civilization is the Indus River valley, a powerful civilization contemporary with Sumer, a civilization that in almost every way surpassed Sumer, and with whom we know for an absolute fact they traded!

For those who don’t know just how awesome the Indus Civilization was, it’s worth a quick detour before we continue.

INDUS VALLEY CIVILIZATION

Indus civilization, the earliest known urban culture of the Indian subcontinent. The nuclear dates of the civilization appear to be about 2600–1900 bce, although the southern sites may have lasted later into the 2nd millennium bce. Among the world’s three earliest civilizations – the other two are those of Mesopotamia and Egypt – the Indus civilization was the most extensive. (Brittanica.com, Indus)

A sophisticated and technologically advanced urban culture is evident in the Indus Valley Civilisation, making them the first urban centre in the region. The high degree of forward-looking urban planning demonstrates the existence of well-organised local governments capable of formulating and executing a large-scale forward-looking development program, and which placed a high value on public health and hygiene, or, alternatively, accessibility to the means of religious ritual.

As seen in Harappa, Mohenjo-daro … this urban plan included the world’s first known city sanitation systems. Within the city, individual homes or groups of homes obtained water from wells. From a room that appears to have been set aside for bathing, waste water was directed to covered drains, which lined the major streets. Houses opened only to inner courtyards and smaller lanes … The Indus Valley cities developed elaborate drainage and sewerage systems, described by archaeologists as well-planned and advanced compared with many contemporary societies. (Wiki, Indus Valley Civilization)

It’s hard to express how cool this culture was, how exceptional among ancient civilizations. They had running water, indoor plumbing, public baths; things not seen again on this level until the time of Rome, and arguably not even then. Things that can be hard to find in that region to this day. Nor was this the extent of their awesomeness:

A prominent feature of most civilizations is evidence of a ruling elite: palatial residences, rich burials, unique luxury products, and propaganda such as monumental inscriptions and portrait statuary or reliefs. Strikingly, all of these are absent from the Indus civilization. This raises the questions of how the Indus state was organized politically, whether there were rulers, and, if so, why they are archaeologically invisible.

Another striking contrast between the Indus and other ancient civilizations is the apparent absence, in the Indus civilization, of any evidence of conflict. Although the cities were surrounded by massive walls, these appear to have functioned as defenses against flooding rather than against hostile peoples, as well as barriers to control the flow of people and goods. They were probably also designed to impress.

Weapons are absent, as are signs of violent destruction during the civilization’s heyday. An entirely peaceful state seems anomalous in the history of world civilization. (Ancient Indus Valley New Perspectives, Mcintosh)

Calling this civilization “anomalous” is a massive understatement. A civilization with indoor plumbing, no apparent weapons of war, no apparent temples or palaces is not rare, it is absolutely unique in the ancient world.

The only massive structures created were public works – no massive monuments to Ramses II, no giant palaces for Nebuchadnezzar and his ruling elite. No evidence of warfare; Indus literally breaks the mold for civilizations, ancient or modern.

Had they existed at the same time, they would have been favorably compared to Rome, but without the whole world-domination thing that the Romans suffered from. In fact, I can’t think of anything larger than a tribal culture that ever existed that didn’t have some form of palace or temple to provide government.

Yet the Indus valley was well governed, and for a long period of time. We can tell this not only by the remarkable city planning, the extensive trade and manufacturing facilities, but also by the system of weights and measures…

In Mesopotamia, comparable standardized systems of weights and measures, on a different standard, were in use by the twenty-third century BCE. These were the result of the standardization of a number of different preexisting systems by the newly unified Akkadian state, and further official standardization was required under the Ur III dynasty after a period of political disintegration had undermined the application of an official standardized system. In contrast, the Indus system of weights and measures was apparently standardized from the start, again suggesting the unity of the Indus state and the existence of a central authority. (Ancient Indus Valley New Perspectives, Mcintosh)

In fact, the uniformity is itself exceptional; what other empire keeps everything the same for so long?

What amazed all these pioneers, and what remains the distinctive characteristic of the several hundred Harappan sites now known, is their apparent similarity: “Our overwhelming impression is of cultural uniformity, both throughout the several centuries during which the Harappan civilization flourished, and over the vast area it occupied.” The ubiquitous bricks, for instance, are all of standardized dimensions, just as the stone cubes used by the Harappans to measure weights are also standard and based on the modular system. Road widths conform to a similar module; thus, streets are typically twice the width of side lanes, while the main arteries are twice or one and a half times the width of streets. Most of the streets so far excavated are straight and run either north-south or east-west. City plans therefore conform to a regular grid pattern and appear to have retained this layout through several phases of building. (India: A History, Keay)

And it was big! Larger than any other city in the world at the time, or any other single civilization.

Mohenjo-daro and Harappa very likely grew to contain between 30,000 and 60,000 individuals, and the civilisation may have contained between one and five million individuals during its florescence. (Wiki, Indus Valley Civilization)

While they did have some sort of a writing system, it has unfortunately never been deciphered; in part because we have no large inscriptions from them, the largest being about 20 characters, the vast majority being seals with 3-4 characters on it, probably names of individuals, making it difficult to decipher.

Because of this, we have no idea what they called themselves; historians call them Harappans, after one of the main cities, or just the Indus Valley Civilization (IVC) for short. But I know who they were, and what they called themselves – and before this chapter is done, I think you will be convinced as well.

LAPIS LAZULI

We can provide conclusive proof that this was, indeed, the civilization known to the Mesopotamians as Aratta by reading more of the story of Enmerkar, and comparing the description in those epics to the facts of the IVC.

In the beginning of the story, the goddess Inanna – no doubt via her high priestess – is pressuring Enmerkar to make demands of Aratta. What she demands tells us what raw materials were available to Aratta:

…let Aratta fashion gold and silver skilfully on my behalf for Unug. Let them cut the flawless lapis lazuli from the blocks, let them …… the translucence of the flawless lapis lazuli ……. …… build a holy mountain in Unug. Let Aratta build a temple brought down from heaven – your place of worship, the Shrine E-ana; let Aratta skilfully fashion the interior of the holy ĝipar, your abode; may I, the radiant youth, may I be embraced there by you. Let Aratta submit beneath the yoke for Unug on my behalf. Let the people of Aratta bring down for me the mountain stones from their mountain. (ELA)

This is clearly the place where the lapis lazuli is quarried, which was highly prized in ancient times – more valuable than gold. And lapis only exists in a very few places in the world, and the only one accessible to Sumerians was in Shortugai, in the Kerano-Munjan district of Afghanistan:

Lapis lazuli was one of the commodities in greatest demand for the decoration of temples and for personal adornment. In the Old World it is found in abundance on the southern shores of Lake Baikal and in the Kerano-Munjan district of Afghanistan. The metamorphic structure of the lapis lazuli found in Sumerian sites in Mesopotamia seems to indicate that it came from Afghanistan, over more than 1200 miles of rugged mountains and extensive desert areas.

As the Sumerians had no political control over either the production centers or the intermediate Iranian plateau, for a good half of the 3rd millennium B.C. these more or less constant supplies were guaranteed by independent centers situated on the plateau, which acted as middlemen in the trade. (Lithic Technology Behind the Ancient Lapis Lazuli Trade; Tosi, Piperno)

First, note that the lapis at Shortugai is the same lapis as the gems that were imported to Mesopotamia. So the fact that somehow, someway, Mesopotamians came this far afield is a scientific fact, not a guess. And based on that lapis mine alone, we can conclusively settle the question by asking “what civilization mined lapis there?”

Shortugai … was a trading colony of the Indus Valley Civilization (or Harappan Civilization) established around 2000 BC on the Oxus river (Amu Darya) near the lapis lazuli mines. It is considered to be the northernmost settlement of the Indus Valley Civilization. (Wiki, Shortugai)

At the top of this picture near the center, you will see that Shortugai is correctly included as part of the IVC, as was everything that could possibly have been in the direction traveled by Enmerkar’s messengers. Anything past the 6th mountain range or so would have been Indus, which is to say Arattan, territory.

Historians know that the Sumerians acquired these stones from Afghanistan, but postulate imaginary “intermediaries.” But textual evidence from Sumer directly contradicts this; remember, Inanna demanded that that Aratta should “bring down the stones from their mountains.”

They were not intermediaries; they mined the stones in their own mountains, worked them in their own factories, and sold them directly to Sumer. Because some of the richest and most diverse deposits of gems and metals in the world is in northern Pakistan. So clearly these were seen to be in the territory of Aratta.

In the same text, Enmerkar demands of the Lord of Aratta “Let him snap off a splinter from it [my scepter] and hold that in his hand; let him hold it in his hand like a string of cornelian beads, a string of lapis lazuli beads. Let the lord of Aratta bring that before me. So say to him.”

It is well agreed by everyone that cornelian stones and the beads made from them in particular were imported to Mesopotamia from the Indus Valley. Once again, we see the association between Aratta and the Indus.

So why don’t the historians already know this? Simply because they are caged by their assumptions regarding the relative ages of these cultures. They date Sumerian culture far too old, for reasons we will explain in another chapter.

They place Enmerkar, if they accept that he really existed at all, around –3100-3400. Obviously, therefore, the Sumerians cannot have traded with a culture that reached its peak in –2600, nor with a gem mine established in –2000. So they are thus prevented from seeing an obvious, conclusive connection which would fix their dating errors.

Because if Enmerkar actually did live around –2200-2100 BC, as we know he did since that’s when Nimrod lived, then the problem mostly disappears; because whether or not the Shortugai site is dated correctly, we know for a fact that Sumerians traded lapis mined at this site. And we know for a fact that Indus people were mining it in those days!

The IVC site at Shortugai was a trading post of Harappan times and it seems to be connected with lapis lazuli mines located in the surrounding area. … typical finds of the Indus Valley Civilization include one seal with a short inscription and a rhinoceros motif, clay models of cattle with carts and painted pottery. Pottery with Harappan design, jars, beakers, bronze objects, gold pieces, lapis lazuli beads, other types of beads, drill heads, shell bangles etc. are other findings. Square seals with animal motifs and script confirms this as a site belonging to Indus Valley Civilisation (not just having contact with IVC). Bricks had typical Harappan measurements. (Ibid)

Fact: Sumer traded Lapis from Aratta.

Fact: Lapis came from “their mountains.”

Fact: That lapis has been matched with the Lapis in Shortugai.

Therefore, therefore Aratta also controlled this site.

Fact: Shortugai was owned by the Indus Valley Civilization.

Therefore: Aratta is the Indus Valley Civilization.

We have much more proof incoming, this is just a start.

THE LORD OF PURIFICATION

Back in Uruk, Innana’s demands for Aratta continued…

Let Aratta pack nuggets of gold in leather sacks, placing alongside it the kugmea ore; package up precious metals, and load the packs on the donkeys of the mountains; and then may the Junior Enlil of Sumer have them build for me, the lord whom Nudimmud has chosen in his sacred heart, a mountain of a shining me; (ELA)

This reflects Enmerkar’s desire to build a “mountain,” i.e., a ziggurat, to honor Inanna, and to do so at the expense of Aratta. But remember, Aratta already is a “mountain of the shining mes,” the mountain of holy gifts; suggesting that, even as they try to topple it, the Sumerians acknowledge that Aratta is their superior!

Who could Nimrod possibly have acknowledged as superior, even as he struggled against them? It must have been those whom everyone knew were the rightful authority of the human race. And in what was certainly a patriarchal society, that could only have been Noah, Shem, and Arphaxad, or at the very least, one of their appointed heirs or rulers.

And so the Lord of Aratta, who is never named in this story, was not intimidated by Enmerkar’s threats, and replied from a position of conscious authority (this passage is worth quoting again):

“Messenger, speak to your king, the lord of Kulaba, and say to him: “It is I, the lord suited to purification, I whom the huge heavenly neck-stock, the queen of heaven and earth, the goddess of the numerous me, holy Inana, has brought to Aratta, the mountain of the shining me, I whom she has let bar the entrance of the mountains as if with a great door. How then shall Aratta submit to Unug? Aratta’s submission to Unug is out of the question!” Say this to him.”… (ELA)

Many interesting things here, but for now let’s talk about the fact that the very first thing the Lord of Aratta identifies himself as is “the lord of purification”; suggesting that to him, that was his most important title. So can it be a coincidence that the most famous feature of the Harappan civilization is called “the great bath,” a massive public bath with no apparent purpose?

The Great Bath of Mohenjo-Daro is called the “earliest public water tank of the ancient world.” 12 metres (40 ft) by 7 metres (23 ft), with a maximum depth of 2.4 metres (8 ft). Two wide staircases, one from the north and one from the south, served as the entry to the structure. (Wiki, great bath)

Most scholars agree that this tank would have been used for special religious functions where water was used to purify and renew the well being of the bathers. This indicates the importance attached to ceremonial bathing in sacred tanks, pools and rivers since time immemorial. (J. M. Kenoyer)

Clearly this is of great ritual significance, built at the same time Enmerkar would have been ruling in Uruk, so clearly “the lord of purification” meant something to people there at the time. And it was lined with bitumen (oil tar), which likely came from Mesopotamia, where it was abundant.

Archaeology has shown us that the IVC culture put baths in nearly every single house; furthermore, there were an astonishing number of private wells, as many as one for every three houses. Clearly this was a culture obsessed with purification. Just like Aratta. It’s worth pointing out the Bible’s concern with purification as well:

Exodus 30:20-21 When they go into the Tent of Meeting, they shall wash with water, that they not die; or when they come near to the altar to minister, to burn an offering made by fire to Yahweh. So they shall wash their hands and their feet, that they not die: and it shall be a statute forever to them, even to him and to his descendants throughout their generations.

MOUNTAIN PASSES

Earlier, the Lord of Aratta boasted “I whom she has let bar the entrance of the mountains as if with a great door.” Taken literally, this means that Aratta controlled the mountain passes, meaning there were narrow ways to get to Aratta from Uruk, and that Aratta controlled the access “as if with a great door.”

This immediately excludes all the scholarly proposals, most of which are somewhere in Iran; because in all of them, if an army were blocked then it could simply approach from a different angle. But the boast of Aratta requires us to look for it behind huge natural barrier.

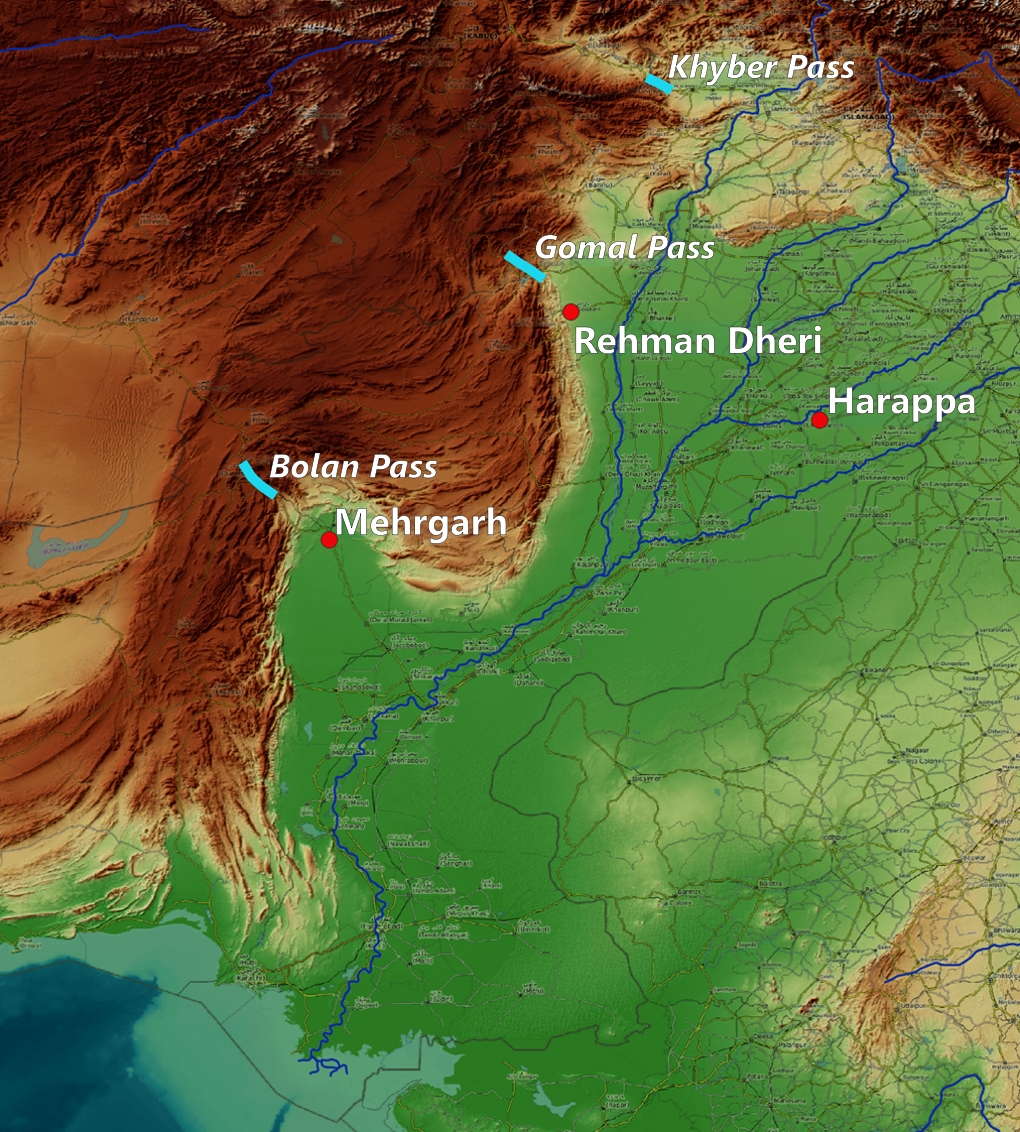

The best possible candidate is the mountain range that runs from the Arabian Sea to the Hindu Kush, forming a nearly impenetrable barrier to the Indus Valley, known as the Sulaiman mountains. There are, to this day, only a few realistic ways to get through those mountains.

From north to south, the passes are called the Khyber, Gomal, and Bolan passes. Which one is specifically meant here is arguable; in practice, the IVC probably controlled all three. Aratta would certainly have had to control the Khyber pass in order to access the lapis lazuli.

The Khyber Pass has historically been a gateway for invasions of the Indian subcontinent from the northwest. Indeed, few passes have had such continuing strategic importance or so many historic associations. Through it have passed Persians, Greeks, Mughals, and Afghans as well as the British, for whom it was the key point for controlling the Afghan border. In the 5th century bce Darius I of Persia conquered the country around what is now Kabul and marched through the Khyber Pass to the Indus River. Two centuries later Hephaestion and Perdiccas, generals of Alexander the Great, probably used the pass. (Britannica, Khyber Pass)

This is one of the few passes through the forbidding mountains that block Pakistan off from the west, and by far the most famous. However, it is unnecessarily far north to continue the line from Susa-Anshan-east. Making the one meant more likely to be the Gomal or Bolan; and for both of these we have clear evidence of IVC fortifications. Controlling the Gomal, we have Rehman Dheri:

Since the earliest occupation, except for the extension outside the city in the south, the entire habitation area was enclosed by a massive wall, built from dressed blocks made from clay slabs. The low rectangular mound is covering about 22 hectares and standing 4.5 meters above the surrounding field.

In the middle of the third millennium BC, at the beginning of the mature Indus phase, the site was abandoned. There was limited reoccupation. … The inscribed seals and sherds of Tochi-Gomal phase may have contributed significantly to the development of the writing system of the mature Indus Civilization. The animals and the symbols depicted on the earliest seal found at Rehman Dheri remind us of the animals and symbols as were portrayed later during the Mature Indus Civilization. (Wiki, Rehman Dheri)

The fact that it was fortified at the very the beginning of the civilization is consistent with a planned defense for invasions from the west, no doubt specifically thinking of Uruk; this attack is actually described later on in the Enmerkar-Arrata stories. But it would do no good to bar one door without the other pass; and for that we have Mehrgarh.

Mehrgarh is a Neolithic archaeological site … located near the Bolan Pass… Mehrgarh is one of the earliest known sites in the Indian subcontinent showing evidence of farming and herding. It was influenced by the Neolithic culture of the Near East, with similarities between “domesticated wheat varieties, early phases of farming, pottery, other archaeological artifacts, some domesticated plants and herd animals.” According to Asko Parpola, the culture migrated into the Indus Valley and became the Indus Valley Civilisation of the Bronze Age.

Jean-Francois Jarrige argues for an independent origin of Mehrgarh. Jarrige notes “the assumption that farming economy was introduced full-fledged from Near-East to South Asia,” and the similarities between Neolithic sites from eastern Mesopotamia and the western Indus Valley, which are evidence of a “cultural continuum” between those sites. However, given the originality of Mehrgarh, Jarrige concludes that Mehrgarh has an “earlier local background,” and is not a “‘backwater’ of the Neolithic culture of the Near East.” (Wiki, Mehrgarh)

This is considered to be the oldest site in the Indus Valley, analogous to Kortik Tepe which we discussed earlier; depending on how early in the settlement of the Indus that Enmerkar attacked (and assuming archaeologists are correct that it is the oldest site), then it’s possible this was Aratta itself, although I would personally favor a more northerly site.

Regardless, what is important is that these two cities effectively bar the gates of the mountains, something that the Lord of Aratta certainly controlled; proving once more that Aratta and Indus were, in the time of Enmerkar, synonymous.

THE BARRIER OF INANNA

Back to the story, the messenger responds that Inanna has told his master that Aratta shall certainly submit, which makes the Lord of Aratta pause for a moment – apparently, they are suffering from a drought and consequent famine at the time, so maybe he has angered the gods? So he responds by saying that, first of all, conquest is impossible; Aratta cannot be beaten militarily:

“Messenger! Speak to your king, the lord of Kulaba, and say to him: “This great mountain range is a meš tree grown high to the sky; its roots form a net, and its branches are a snare. It may be a sparrow but it has the talons of an Anzud bird or of an eagle. The barrier of Inana is perfectly made and is impenetrable (?).”” (ELA)

This fits well with the Hindu Kush and the Sulaiman mountain range, but not to the mountains nearer to Sumer or in the Iranian highlands where most historians would place this. None of them constitute a “perfectly made … impenetrable” barrier. They are, in fact, quite porous, albeit rugged in spots.

But the Pakistani/Iranian border does make just such a barrier, and we can prove that Indus/Aratta controlled the passes and the lapis mines beyond. So knowing this, the Lord of Aratta is quite confident he cannot be beaten unless the gods do it, in which case he shouldn’t fight them.

So the Lord of Aratta says that if Enmerkar can prove that Inanna is with him, he will submit; so he devises a test, asking for grain to be sent to Aratta in fishing nets; obviously, this is impossible, so he thinks himself quite clever. Enmerkar then sprouts some grain first, using the grass that grows from the grain to hold in the rest of the grain in the sacks.

Despite his brilliance, Aratta still refuses to submit and makes two more challenges, each of which is handled by Enmerkar. The story is fragmented at the end; some readings seem to have Aratta submitting, some have Enmerkar admitting failure after losing the final challenge, but regardless it is clear that Aratta sent a significant amount of gems and valuables, whether as tribute or in trade.

THE LORD OF ARATTA

The “matter of Aratta” consists of a total of four separate episodes, and as we move to the second one, we find the Lord of Aratta finally has a name; hence this book is called Enmerkar and Ensuhkeshdanna (which we’ll cite as EE).

This name doesn’t match anyone in the Bible, unfortunately, but we can indirectly confirm it must be a very high ranking son of Noah, perhaps Shem, himself – because like many ancient “names,” it’s not a name as we understand the term, but a title. The name breaks down as follows

𒂗 𒋗𒆠𒊺 𒁕 𒀭𒀀𒈾

en – šuh – kiš – da – an – na

You may notice that third element is “kish,” just like the city, “pure like Kish and Aratta.” The generally agreed translation is “The lord who is purified in Kish, by (the authority of) An (u).” However, ancient languages and grammar being what it is, and given the fact that Aratta seems to be even more holy than Kish, I would suggest the following reading:

“The lord who purified Kish, by (the authority of) An (u)”

This puts an entirely new slant on the name; because the Lord of Aratta clearly considers the idea of submitting to Uruk laughable; because even Kish existed only because the Lord of Aratta blessed the kingship of Etana.

I struggle to believe that, even in the face of famines and such, Enmerkar could have intimidated Noah; however, I can more easily believe that Shem was swayed by his chest-thumping. Further, Kish was an ethnically Semite, not Sumerian, city.

… Enmerkar ruled after the long and eminent Semitic dynasty of Kiš, after Enmebaragsi and Akka. (Ups and downs in the career of Enmerkar, Dina Katz)

Shem, as the leader of the three brothers, would naturally be the one who had to sign off on the building of the first city; the appointment of the non-Semite Etana as the first king doesn’t necessarily contradict that fact since it was a city for the whole family of man.

After the division of languages, however, Sumerians (Cushites) went south, and Shemites went north; making Kish forever after a Semite city. If, as we believe, Shem went with his firstborn Arphaxad to the Indus valley, then Shem could legitimately be titled “The lord who purified Kish, by (the authority of) An (u).”

After all, Shem means “name,” in the sense of fame or authority. Who better could be said to have the “name,” than he “whom the huge heavenly neck-stock, the queen of heaven and earth, the goddess of the numerous me, holy Inana, has brought to Aratta.”

Obviously, we find his reverence of Inanna problematic, if we identify him as righteous; but there are two options; this was, after all, a Babylonian story. They may have simply placed reverence for the queen of heaven in his mouth when telling the story back home. He may have literally said “I whom the almighty God has brought to Aratta,” and Enmerkar edited it back home.

We can support this with two pieces of evidence; first, in the opening lines of ELA, Inanna complains

The lord of Aratta placed on his head the golden crown for Inana. But he did not please her like the lord of Kulaba. Aratta did not build for holy Inana – unlike the Shrine E-ana, the jipar, the holy place, unlike brick-built Kulaba. (ELA)

We know the Indus Valley lacked temples; the lack of a temple to Inanna would argue that Aratta was less idolatrous, despite the fact that Inanna is mentioned reverently many times later in these stories, that might have been the Babylonians inserting that praise into their “rebellious” rivals’ mouths.

Another ancient story about Aratta has her attacking a mountain/god called “Ebih”; most scholars place this in northern Iraq, but as far as I can tell they have no clear reason to place the mountain there… Particularly when they conveniently ignore that the target of her anger was Aratta.

When I, the goddess, was walking around in heaven, walking around on earth, when I, Inana, was walking around in heaven, walking around on earth, when I was walking around in Elam and Subir, when I was walking around in the Lulubi mountains, when I turned towards the centre of the mountains, as I, the goddess, approached the mountain it showed me no respect, as I, Inana, approached the mountain it showed me no respect, as I approached the mountain range of Ebiḫ it showed me no respect.

Since they did not act appropriately on their own initiative, since they did not put their noses to the ground for me, since they did not rub their lips in the dust for me, I shall fill my hand with the soaring mountain range and let it learn fear of me.

Against its magnificent sides I shall place magnificent battering-rams, against its small sides I shall place small battering-rams. I shall storm it and start the ‘game’ of holy Inana. In the mountain range I shall start battles and prepare conflicts.

I shall prepare arrows in the quiver. I shall …… slingstones with the rope. I shall begin the polishing of my lance. I shall prepare the throw-stick and the shield. I shall set fire to its thick forests. I shall take an axe to its evil-doing. I shall make Gibil, the purifier, do his work at its watercourses. I shall spread this terror through the inaccessible mountain range Aratta.

Inanna reaches Biblical levels of fury for their lack of idolatry to her. And whether or not her direct target is Aratta, they are clearly lumped in with these disrespectful rebels who “showed me no respect,” who “did not put their noses to the ground for me, since they did not rub their lips in the dust for me.”

This suggests that Aratta was not an Inanna worshiper, regardless of what the stories have the Lord of Aratta saying. Then again, it’s certainly possible that Shem may have been deceived, to a point; how many “righteous kings” of Israel served Yahweh, yet did not remove the high places? Jehoshaphat, for instance, of whom many good things were said; yet…

1 Kings 22:43 He walked in all the way of Asa his father; he didn’t turn aside from it, doing that which was right in the eyes of Yahweh: however the high places were not taken away; the people still sacrificed and burnt incense in the high places.

God can overlook a lot, when things are done in ignorance (Acts 17:30). Regardless, we have plausible reason to connect Shem to Aratta, precisely where we expected to find him. And if not Shem, we can easily believe this might be Arphaxad; after all…

Aratta might actually be his name.

Even today, when a name passes from one language to another, it changes. George becomes Jorge, Ekaterina becomes Catherine, etc. Generally because the target language has no sound like the origin language, so it makes the closest approximation it can; and sometimes just because the target language is lazy; which is how Moskva became Moscow and Napoli became Naples.

And the name Arpakhshad, as it’s more literally rendered from Hebrew, presents nothing but problems for Sumerian, which lacks many of the basic sounds of Hebrew; it would have been literally impossible to spell the name Arpakhshad in Sumerian and have it sound anything like the original name.

First of all, there is no “p” or “kh” sound in Sumerian; they not do have consonant clusters like khsh; and the final closed syllable (-ad) would probably have been dropped or changed, as we already saw with the name Nimrod (the hunter) which became Enmer (kar).

Thus, Sumerian scribes would have been forced to greatly simplify the name into their language, meaning it would have gone through an evolution as follows: Arpaḵšad → Arakad → Aratad → Aratta.

Which means if we assume that the enemy’s name was indeed Arphaxad, Enmerkar would have had no choice but to write it down in a greatly changed form which would very likely have been… Aratta.

This is part 7 of The History of the World Series