In the next chapter of the Enmerkar-Aratta saga, which scholars call Enmerkar and Ensuhkeshdanna, we find Aratta not only unsubmissive, but actively demanding that Uruk submit to it! Ensuhkeshdanna is apparently overconfident and demands that Enmerkar submit to Aratta. Naturally, Enmerkar refuses and makes threats, which makes Aratta have second thoughts.

Again, this was a Sumerian story. I’d love to hear the Arattan version because I’m quite sure these facts have been through the spin factory, but this is all we have. Anyway, the Lord of Aratta’s counselors tell him he bit off more than he can chew, and just when he’s starting to really worry, a sorcerer comes and offers to make Uruk [Unug] submit for him:

I will make Unug dig canals. I will make Unug submit to the shrine of Aratta. After the word of Unug ......, I will make the territories from below to above, from the sea to the cedar mountain, from above to the mountain of the aromatic cedars, submit to my great army. Let Unug bring its own goods by boat, let it tie up boats as a transport flotilla towards the E‑zagin of Aratta. (EE)

What’s particularly interesting for us, trying to locate Aratta, is that we now know goods can be transported entirely by boat from Uruk to Aratta. This completely eliminates all of the options of historians, since there’s no way to get to Afghanistan or central Iran or Armenia, or anywhere in between, with a merchant ship. You can’t even get close. There is literally only one place…

- Across seven mountain chains in the direction of Susa and Anshan (east)

- The lapis mines in Afghanistan are within its territory, along with many other precious metals and jewels

- On the far side of mountain passes, which it controls

- And it’s also reachable entirely by boat

It’s time for another map.

So you see, there is a perfectly natural way to reach there – by boat from Uruk, out the Persian Gulf, and up the Indus River. Precisely how we know for a fact the Harappans traded with Uruk!

It seems, however, that Harappan participation in the trading networks right across the Iranian plateau, which depended on the use of pack animals, virtually ceased, and was replaced by trade using water transport. Though not without its risks, such as storms and perhaps pirates, this was generally an easier and more efficient means of transporting goods, particularly bulky or heavy materials. Direct seaborne communications through the Gulf were now established between the Indus civilization and Mesopotamia, the main Near Eastern consumer of imported raw materials. This link enabled the Harappans to conduct direct commercial relations with Mesopotamia, giving them direct control over the management of their trade rather than depending on intermediaries (as the land traffic had) and thereby improving both their returns on their exports and their ability to control the supply of imports. Sea trade also gave the Harappans access to the resources and markets of the cultures in the Gulf. The establishment of new Harappan settlements along the Makran coast reflected the development of this maritime trade (Ancient Indus Valley New Perspectives, McIntosh).

The existence of these “intermediaries” is, as far as I can tell, purely hypothetical; no particular accumulation of Harappan goods has ever been found in the parts of Iran where such intermediaries would have lived. They are figments of the imaginations of historians, in direct contradiction to contemporary records.

There almost certainly existed two separate, independent routes – one by land, one by sea – probably from the very beginning. Each had their own advantages and disadvantages, as shown by the fact in the Enmerkar cycle that both land messengers/land invasions as well as sea trade are depicted.

THE STORY CONTINUES

Anyway, the sorcerer having been sent to Uruk, he curses the dairy cows; fortunately, Uruk finds its own sorcerer, who wins several challenges and in the end kills the first sorcerer. The conclusion is clear:

Having heard this matter, En-suhgir-ana sent a man to Enmerkar: “You are the beloved lord of Inana, you alone are exalted. Inana has truly chosen you for her holy lap, you are her beloved. From the south to the highlands, you are the great lord, and I am only second to you; from the moment of conception I was not your equal, you are the older brother. I cannot match you ever.” In the contest between Enmerkar and En-suhgir-ana, Enmerkar proved superior to En-suhgir-ana. Nisaba, be praised! (Enmerkar and En-suhgir-ana)

The acknowledgment as “the older brother,” as a sign of respect, arguably suggests the reverse was the real truth; that Enmerkar was younger than the Lord of Aratta, consistent with him being Shem or Arphaxad or even Salah, and possibly Eber; whoever it was, he was abasing himself before his junior.

Again, that’s how the Sumerians told it; I’m skeptical that it went down this way since in the next installment, called Lugalbanda and the Mountain Cave (LMC), Enmerkar has launched a full scale land invasion containing as many as 200,000 men. So maybe Enmerkar exaggerated his success a bit in the previous chapter?

…now at that time the king set his mace towards the city, Enmerkar the son of Utu prepared an ...... expedition against Aratta, the mountain of the holy divine powers. He was going to set off to destroy the rebel land; the lord began a mobilization of his city. The herald made the horn signal sound in all the lands. (LMC)

Note the curious contradiction here; Aratta is called “the rebel land,” and yet is simultaneously seen as “the mountain of the holy divine powers.” An odd mix of reverence and scorn. But precisely what we would expect Enmerkar to tell his people.

Remember, he was trying to justify challenging the people everyone knew had been appointed to rule; casting them as the rebels was impossible unless he could prove that they had been rebellious against the gods. Hence the repeated mentions of how “Inanna likes me best.”

Now levied Unug took the field with the wise king, indeed levied Kulaba followed Enmerkar. Unug’s levy was a flood, Kulaba’s levy was a clouded sky. As they covered the ground like heavy fogs, the dense dust whirled up by them reached up to heaven. As if to rooks on the best seed, rising up, he called to the people. Each one gave his fellow the sign.

At that time there were seven … They were heroes, living in Sumer, they were princely in their prime. They had been brought up eating at the god An’s table. These seven were … overseers of 300 men, 300 men each; they were captains of 600 men, 600 men each; they were generals of 7 car (25,200) of soldiers, 25,200 soldiers each. They stood at the service of the lord as his élite troops. (LMC)

Granting that this might well be an exaggeration, nonetheless no amount of boats could realistically transport an army of that scale. Hence, a land invasion through one of the passes. The 1200 mile journey was not trivial, but if the land was wetter at the time – and scientists believe that it was – it would be quite doable.

Interestingly, propaganda or no, the invasion was not depicted as successful, and the hero of these stories is about to shift to Lugalbanda, Enmerkar’s immediate successor as king of Uruk in the SKL – and very likely the messenger of the first two books. Here, when we meet him by name for the first time, he is the 8th general in his elite troops…

Lugalbanda, the eighth of them, ...... was washed in water. In awed silence he went forward, ...... he marched with the troops. When they had covered half the way, covered half the way, a sickness befell him there, ‘head sickness’ befell him. (LMC)

The story largely focuses on his being left in a cave to recover or die by his comrades, being healed and having a vision and a dream, making some sacrifices, then a long description of evil spirits and their ways, then concluding with some poetic stuff about the gods and their role in warfare on the side of the good guys. The end of the tablet is badly damaged so it’s hard to know for sure what the point was.

LUGALBANDA AND THE ANZUD BIRD (LAB)

The fourth story seems to be a continuation of the third, and begins with Lugalbanda alone in the wilderness; it seems he’s lost, and wants to reconnect with the army of Uruk, his brothers, and see what happened to them. To do so, he concocts a plan to do a favor for a magical Anzud-bird; capable of carrying an entire bull in its claws, with teeth like a shark’s.

When the bird has drunk the beer and is happy, when Anzud has drunk the beer and is happy, he can help me find the place to which the troops of Unug [Uruk] are going, Anzud can put me on the track of my brothers. (LAB)

Long story short, he is nice to the Anzud bird’s chick, and when the great bird arrives home after a day hunting cattle, he at first is worried that the chick doesn’t answer, then relieved to see that Lugalbanda has taken such good care of his nest. The bird says…

The bird is exultant, Anzud is exultant: “I am the prince who decides the destiny of rolling rivers. I keep on the straight and narrow path the righteous who follow Enlil’s counsel. My father Enlil brought me here. He let me bar the entrance to the mountains as if with a great door. If I fix a fate, who shall alter it? If I but say the word, who shall change it? Whoever has done this to my nest, if you are a god, I will speak with you, indeed I will befriend you. If you are a man, I will fix your fate. I shall not let you have any opponents in the mountains. You shall be ‘Hero-fortified-by-Anzud.’” (LAB)

Lugalbanda, in typical hero fashion says he was just trying to be nice, and doesn’t want a reward. The bird offers him various typical reward stuff; money, power, you know the drill. Lugalbanda politely declines; finally the bird demands that he tell him what he wants. He asks for physical endurance, of all things.

Holy Lugalbanda answers him: “Let the power of running be in my thighs, let me never grow tired! Let there be strength in my arms, let me stretch my arms wide, let my arms never become weak! Moving like the sunlight, like Inana,” … (LAB)

He goes on like that for awhile. Considering how much work it took to write a tablet, ancient stories were really repetitive sometimes. Anyway, he is of course granted his wish and sets off to join the troops of Uruk. They are excited to see him, wanting to know what happened, but the Anzud-bird swore him to secrecy so he is evasive. Our part of the story continues…

Then the men of Unug followed them as one man; they wound their way through the hills like a snake over a grain-pile. When the city was only a double-hour distant, the armies of Unug and Kulaba encamped by the posts and ditches that surrounded Aratta. From the city it rained down javelins as if from the clouds, slingstones numerous as the raindrops falling in a whole year whizzed down loudly from Aratta’s walls. The days passed, the months became long, the year turned full circle. A yellow harvest grew beneath the sky. (LAB)

These clues tell us that the battle lasted at least a year; which also tells us, in turn, this battle was not confined to the mountain passes, where no army could have held siege through the winter. So this must have taken place somewhere in the cities of the Indus Valley, where “a yellow harvest” (some form of grain) grew, where “ditches” were dug (for irrigation).

My best guess is Mehrgarh, according to archaeologists, the oldest of the cities; if they’re right, then it’s probably Aratta, but that’s just a slightly educated guess. It fits many of the themes – near the mountain passes, in a valley with irrigation, closest to Uruk by land than any other Indus city, with pottery and technology definitively tied to Mesopotamian:

Mehrgarh is one of the earliest known sites in the Indian subcontinent showing evidence of farming and herding. It was influenced by the Neolithic culture of the Near East, with similarities between “domesticated wheat varieties, early phases of farming, pottery, other archaeological artifacts, some domesticated plants and herd animals.” According to Asko Parpola, the culture migrated into the Indus Valley and became the Indus Valley Civilisation of the Bronze Age. (Wiki, Mehrgarh)

So it’s a good fit, but it’s by no means conclusive. It could have been any of the five great cities of the Indus Valley, none of whose original names we know. If it isn’t Mehrgarh, my best pick would be Harappa itself. Regardless, returning to the tale of the siege, we find it not going well;

They looked askance at the fields. Unease came over them. Slingstones numerous as the raindrops falling in a whole year landed on the road. They were hemmed in by the barrier of mountain thornbushes thronged with dragons. (LAB)

The presence of “mountain” bushes suggests a mountain location; the reference to dragons is interesting, keep that in mind for when we discuss Humbaba and Gilgamesh in the next chapter. Meanwhile Enmerkar – mentioned for the first time in almost two whole “chapters” – is in a state of despair:

No one knew how to go back to the city, no was rushing to go back to Kulaba. In their midst Enmerkar son of Utu was afraid, was troubled, was disturbed by this upset. He sought someone whom he could send back to the city, he sought someone whom he could send back to Kulaba. No one said to him “I will go to the city.” No one said to him “I will go to Kulaba.” He went out to the foreign host. No one said to him “I will go to the city.” No one said to him “I will go to Kulaba.” He stood before the élite troops. No one said to him “I will go to the city.” No one said to him “I will go to Kulaba.” (LAB)

Basically, since he had spent a year failing to conquer a city that Inanna had sent him to conquer, he was starting to question her wishes; indeed, questioning her good faith – she was worshiped, but not always trustworthy, this goddess. And no one felt like volunteering for an extremely dangerous journey like that.

Naturally, Lugalbanda with his gift of endurance volunteered to go, and to go alone at that. After the expected hemming and hawing, Enmerkar agrees – he is desperate, after all; and gives him the following message:

After he had stood before the summoned assembly, within the palace that rests on earth like a great mountain Enmerkar son of Utu berated Inana: “Once upon a time my princely sister holy Inana summoned me in her holy heart from the bright mountains, had me enter brick-built Kulaba. Where there was a marsh then in Unug, it was full of water. Where there was any dry land, Euphrates poplars grew there. Where there were reed thickets, old reeds and young reeds grew there. Divine Enki who is king in Eridu tore up for me the old reeds, drained off the water completely. For fifty years I built, for fifty years I was successful. Then the Martu peoples, who know no agriculture, arose in all Sumer and Akkad. But the wall of Unug extended out across the desert like a bird net. Yet now, here in this place, my attractiveness to her has dwindled. My troops are bound to me as a cow is bound to its calf; but like a son who, hating his mother, leaves his city, my princely sister holy Inana has run away from me back to brick-built Kulaba. If she loves her city and hates me, why does she bind the city to me? If she hates the city and yet loves me, why does she bind me to the city? If the mistress removes herself from me to her holy chamber, and abandons me like an Anzud chick, then may she at least bring me home to brick-built Kulaba: on that day my spear shall be laid aside. On that day she may shatter my shield. Speak thus to my princely sister, holy Inana.” (LAB)

This gives us several interesting bits of information about the Biblical Nimrod; he plainly says that he built Uruk, that before him it was just a marsh, when Inanna “summoned” him “from the bright mountains.” Presumably, this is how Nimrod understood the migration from Gobekli Tepe to Babel.

Nimrod also looks back on a successful career which lasted over 50 years – presumably not counting that awkward Babel fiasco. Then, it says, the Martu people rebelled; these were also called the Amurru, or the Biblical Amorites, who dwelt far to the west in the area of Canaan.

It’s worth noting that they are recorded in the Sumerian Kinglist as the Dynasty of Mari, which probably relates to the time of this war. It is certain that the Mari were a powerful kingdom at this time in history, close enough to and capable of attacking Sumer.

Uruk was able to withstand this attack thanks to a large wall Enmerkar had built. But now, after all this success – while attempting to force Aratta to provide her with goods for her temple, no less – now Inanna has given up on him, he laments, leaving him to die in Aratta. If that’s the case, he says, he’ll gladly retire – just bring him home.

Laden with this message, Lugalbanda makes it home in record time, sees Inanna who it seems immediately falls in love with him, laying the groundwork for him being the next king (which he was); then Inanna tells Lugalbanda to tell Enmerkar that if he cuts a certain tamarisk growing in a marsh by itself, then catches and sacrifices a certain fish…

…then his troops will have success for him; then he will have brought to an end that which in the subterranean waters provides the life-strength of Aratta.” “If he carries off from the city its worked metal and smiths, if he carries off its worked stones and its stonemasons, if he renews the city and settles it, all the moulds of Aratta will be his.” Now Aratta’s battlements are of green lapis lazuli, its walls and its towering brickwork are bright red, their brick clay is made of tinstone dug out in the mountains where the cypress grows. Praise be to holy Lugalbanda. (LAB)

The story ends there; we don’t know if that worked or not; what we do know is that Lugalbanda, not the aging Enmerkar, is clearly the subject of the story by the end; in fact, we can see the entire saga as slowly building up to legitimize Lugalbanda in favor of Enmerkar.

That’s why the final conclusion is “praise be to holy Lugalbanda,” a title never accorded to Enmerkar in these stories. Given the way that the Enmerkar cycle ended, and how Lugalbanda replaced him, we might speculate that Enmerkar did not follow Inanna’s instructions properly and failed to take Aratta – in fact, it seems likely that Enmerkar never returned from Aratta:

The author chose the only Sumerian cultural hero, whose activities are recorded only by three tales. Otherwise Enmerkar does not appear in inscriptions or god lists. The paucity of material is incompatible with his status as a king in the Sumerian tales. Moreover, Enmerkar was not deified like his successors Lugalbanda and Gilgameš despite his proclaimed divine ancestry. Since the Babylonians believed that the dead ancestor turns into a personal god by force of a proper funerary ritual, not being deified would suggest to them that he did not even have the traditional cult of the ancestors. A Babylonian would then conclude that either Enmerkar died in the wilderness or on the battlefield. Both cases would be regarded as a punishment. Death on the battlefield, however, would mean that he ignored the will of the gods, which is revealed in divination. (Ups and downs in the career of Enmerkar, Dina Katz)

The gods clearly favored Lugalbanda more than Enmerkar by the end of the stories; needing to explain why Enmerkar did not return from Aratta would be very important to the Sumerian worldview. Hence his replacement with Lugalbanda, who was “brought up eating at the god An’s table… Lugalbanda, the eighth of them, ...... was washed in water.”

Being “washed in water” is certainly a purification ritual akin to Christian baptism, and most likely this means he was raised in the temple as a priest, a position which overlapped heavily with that of king in those days, and thus was set up to be taken as consort of Inanna and become the rightful ruler of Uruk.

THE SIN OF ENMERKAR

In later Babylonian mythology Enmerkar is seen as something of a failure – despite his status as first king of Uruk. Historians are unable to explain this. The actual text is as follows…

Whoever sins against the gods of that city, his star shall not stand in the sky, his kingship will end, his scepter will be taken away, his treasury will become a heap of ruins [...]. And the king of heaven and earth said thus: “The gods of heaven and earth [...] the behavior of each former king of which I hear to [...]. Akka, son of [...] Enmerkar, king of Uruk, destroyed the people [...]. The sage Adapa, son of [...] heard in his holy sanctuary and cursed Enmerkar.” (Weidner Chronicle)

This chronicle dates to the Isin dynasty, probably 500-700 years after these events. Among other things, it makes a list of proverbial sinners and failures, and includes Enmerkar as one who “destroyed the people” in some undefined way, but clearly by “sinning against the gods.” One scholar explains this passage as follows…

The bad reputation of Enmerkar followed him to the Weidner Chronicle. Unfortunately the passage in the chronicle that refers to him is fragmentary. It is clear that Enmerkar committed a sin, but its nature unknown. The Chronicle is about the cult of Marduk in Esagila which means that the offense took place in Babylon. The remains of the text indicate that he was cursed by Adapa. I cannot explain how these two characters could meet outside the bookshelves. The one is an antediluvian character, and the other postdiluvian. The location in Babylon is anachronistic, far detached from the Sumerian literary landscape, as if the dimensions of time and place shrank. Is it possible that the chronicle is based on an unknown old tradition that considered Enmerkar as a contemporary of Adapa, but went out of hand? (Ups and downs in the career of Enmerkar, Dina Katz)

This scholar is rightly confused why Enmerkar has a bad reputation; why he was never deified in Sumer even though he was the grandson of a god, especially when his successors were.

They are especially confused as to why he is connected to Babylon which – according to them – would not even be founded for hundreds of years after he died. Only if one believes the Bible can we make sense of this, for the offense of Enmerkar/Nimrod did indeed take place at Babylon and later generations remembered it!

BACK TO THE POINT

Having fleshed out the story of Enmerkar and located Aratta, we are now finally ready to bring the point home; Aratta is the civilization of the Indus Valley. It checks literally every box, and everyone would know this if their chronology was not off by upwards of a thousand years. That is literally the only obstacle – hence my focus on chronology.

And as final proof that Aratta is indeed the civilization of the Indus Valley, I call as witness not one, but two utterly unrelated sources, untouched by any sort of Babylonian or Biblical narrative; first we call their neighbors to the south of the Indus region, the Hindus.

Aratta (आरट्ट) is an ancient tribe and janapada mentioned in Mahabharata, Mahavansha, Vedas, Ashtadhyayi of Panini etc. This is a Prakrit form of the Sanskrit Arashtra (आराष्ट्र). Aratta is a land that appears in Vedas. (JatlandWiki.com, “Aratta”)

It is agreed by all, based on internal evidence in the ancient Indian books, to be in the Punjab region, which is to say, in the upper Indus Valley. Historians reject the connection with the Aratta of Sumer out of hand; with simple dismissal, not even worthy of argument:

By 1973, archaeologists were noting that there was no archaeological record of Aratta’s existence outside of myth, and in 1978 Hansman cautions against over-speculation. Writers in other fields have continued to hypothesize potential Aratta locations. A “possible reflex” has been suggested in Sanskrit Āraṭṭa or Arāṭṭa mentioned in the Mahabharata and other texts. (Wiki, Aratta)

A reflex, in this sense, means a linguistic carry-over through the ages; in other words, a name used by one civilization that was continued to be used by the one that replaced it. To historians, the simple coincidence of two places with the same name doesn’t mean much; and that’s fair, on its own.

To them, these civilizations are separated by thousands of years, and they don’t believe Aratta could be that far away in the first place. But since we’ve already proven, in half a dozen ways, that Aratta must be the Indus… it then becomes a valid confirmation that their Indian neighbors to the south likewise remembered the name.

Our second witness is the Greeks; in a document called the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, a map-like handbook text for Roman/Greek traders in the first century plying the Arabian and Indian waters.

…As the people of Aratta fetched the lapis out of their highlands, we may further suggest that in part, Aratta was identified with areas of Afghanistan. This point, perhaps, gains further support from a passage in the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea where it is stated that the Arattii people live in regions where the Arochosii are also to be found [see picture at rightabove, just to the right of “PERSIA”]. Now the Arochosii people are known to have occupied the country around the modern town of Kandahar in eastern Afghanistan and in this context of usage we may consider that the Arattii lived near the Arochosii and that this first name given a Greek ending in a Greek text attests a people who resided in the ancient land of Aratta. If this is correct, we may then suggest that Aratta was indeed, in part, to be found in the vicinity of Shahr-i Sokhta, which lies in Iran near the western border of Afghanistan. (The Question of Aratta, Hansman)

This author comes close to guessing the right answer but, guided by scholarly consensus, places the Aratti on the wrong side of the Arachosii; they were not to the west of them in Afghanistan or Iran, but to the east of them in Pakistan, precisely where the Hindu sacred texts place them.

ARYANS

Nor is that all; although this next part is particularly contentious. The NW part of India and Pakistan is known to have a strong Indo-European connection; linguistically, culturally, and ethnically the ancient peoples of Iran and Pakistan were connected.

The Indo-Aryan migrations were the migrations into the Indian subcontinent of Indo-Aryan peoples, an ethnolinguistic group that spoke Indo-Aryan languages. These are the predominant languages of today’s Bangladesh, Maldives, Nepal, North India, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.

Indo-Aryan migration into the region, from Central Asia, is considered to have started after 2000 BCE as a slow diffusion during the Late Harappan period and led to a language shift in the northern Indian subcontinent. Several hundred years later, the Iranian languages were brought into the Iranian plateau by the Iranians, who were closely related to the Indo-Aryans. (Wiki, Aryans)

This is very politically charged due to the impact it has on the claims of India and Pakistan to the rights of certain regions in the area; and because the Indians would prefer to believe that the Europeans came from India, while the Europeans would prefer to believe that the Indians came from Europe (or rather, a common center in Turkey).

Also, obviously, the term Aryan is tainted because the Nazis used this theory to claim that they were in fact the Aryans, born to rule the world as a master race. Both of which are immaterial to the facts here, but which make it hard to talk about – and hard to know whose opinion to trust.

These Indo-Aryan speaking people were united by shared cultural norms and language, referred to as ārya, “noble.” Diffusion of this culture and language took place by patron-client systems, which allowed for the absorption and acculturation of other groups into this culture, and explains the strong influence on other cultures with which it interacted. (Ibid)

Note that their language/culture was Arya, which meant “noble.” Now you may recall that Aratta was used as a substitute noun meaning “splendid, important,” etc. And for Aratta to be corrupted or translated into Arya is very easy to imagine.

Once again, linguistic similarities alone are not convincing; but when we already know that Arattans were there, at the right place at the right time, just before the Aryans began migrating… we have strong reason to suspect that the Aryans are the Arattans.

That in turn is also interesting because the name “Iran” literally means Aryan. It’s the same word spelled differently.

The word ērān [Iran] is first attested in the inscriptions that accompany the investiture relief of Ardashir I (r. 224–242) at Naqsh-e Rustam.[1] In this bilingual inscription, the king calls himself “Ardashir, king of kings of the Aryans” …The Middle Iranian ērān/aryān are oblique plural forms of gentilic ēr - (Middle Persian) and ary - (Parthian), which in turn both derive from Old Iranian *arya-, meaning “‘Aryan,’ i.e., ‘of the Iranians.’” This Old Iranian *arya - is attested as an ethnic designator in Achaemenid inscriptions as Old Persian ariya-, and in Zoroastrianism’s Avesta tradition as Avestan airiia-/airya, etc. It is “very likely” that Ardashir I’s use of Middle Iranian ērān/aryān still retained the same meaning as did in Old Iranian, i.e. denoting the genitive case of the ethnonym rather than a proper toponym. (Wiki Iran [Name]).

We can then begin to tell a story, a far better one than historians tell, of how the IVC Arattans, whose civilization for some reason suddenly collapsed, fled; perhaps because of war, famine, or climate change (see, I can call up the usual suspects as well).

They went elsewhere; probably under pressure from tribes to the south, the northerly tribes fled into Iran; where else were they to go? History and archaeology remembers this as the Aryan migration, although they usually have the story backwards. These people came into Iran, not out of it.

While there, they split into a multitude of tribes, probably reflecting their origin cities or family tribes, known to history as the Medes, Persians, and Parthians. But more on that in its proper place. Meaning that these peoples would claim descent from the eldest son of Shem, Arphaxad.

Meaning that if this is true, Arphaxad wound up just on the eastern border of his brother Elam; precisely as we would expect based on the sequence of Lud-Aram-Assur-Elam-Arphaxad. Shem’s territories were, therefore, contiguous from the very beginning, just as Ham’s were to the west.

Precisely as you’d expect.

THE PRIEST-KING

To put a bow on this, let’s connect the nature of Arphaxad’s known descendants, the Hebrews, to the known practices of Arattans and the IVC. In the Enmerkar story, his nemesis the Lord of Aratta doesn’t really mean “lord” in the sense we understand it, but more like priest-king. The primary scholar who translated the text says…

As for Aratta’s political organization, we note its head and ruler was the en, “lord,” or perhaps “high-priest” (the title “king” seems to be unknown in Aratta, and it is noteworthy that Enmerkar, too, was known primarily by the title en, although he is described as lugal, “king,” several times in our poem (see lines 306, 311, 316, etc.). (ELA commentary, Samuel Kramer)

How fitting for a culture with no visible rulers, no palace and no evident temple, to not have a king! This is an extremely solid connection between the IVC, Aratta, and the way we would expect the original Hebrew, Eber,to organize his government; just like the Hebrews did in Canaan.

In Canaan, for around four centuries, the Hebrews had no king, no palace; only a system of judges and elders. A king speaks for himself, and rules in his own name. A priest-king speaks for his god, and rules – theoretically at least – in the name of his god.

1 Samuel 12:12 … ye said unto me [Samuel], Nay; but a king shall reign over us: when the LORD your God was your king.

Moses was clearly a priest of sorts – he was free to enter the temple at will – but he was also the leader of the people. As were Joshua, Gideon, and so on. The last of these judges was Samuel; all of these were the undeniable leaders of Israel, but none were seen as doing this on their own authority, but as a mouthpiece for God. So if we characterize Moses and Samuel as priest-kings, we cannot be far wrong.

I say all this because when Enmerkar addresses the leader of Aratta as “the en of Aratta,” he is addressing him as a fellow priest-king. No, as an elder priest-king, the rightful priest-king seated “in the mountain of holy powers.”

But Enmerkar characterizes the lord of Aratta as a priest-king who is not beloved by his goddess, making himself the only true priest, and therefore rightful king. While I’m not convinced that the Arattans actually worshiped Inanna, it is clear that Nimrod was casting down a challenge of divine approval, just like the rebels in the wilderness did with Moses:

Numbers 16:2-3 [Korah and other Levites] … rose up before Moses, with certain of the children of Israel … and they assembled themselves together against Moses and against Aaron, and said to them, “You take too much on yourself, since all the congregation are holy, everyone of them, and Yahweh is among them: why then lift yourselves up above the assembly of Yahweh?”

Moses proceeded to ask God to choose between them, and make it clear which leader He wanted:

Numbers 16:5-7 and he spoke to Korah and to all his company, saying, “In the morning Yahweh will show who are his, and who is holy, and will cause him to come near to him: … and it shall be that the man whom Yahweh chooses, he shall be holy. You have gone too far, you sons of Levi!”

Thus even if we accept that the names of the deities may have been changed/inserted later by Sumerians (Yahweh replaced with Inanna, perhaps), it’s still clearly a younger would-be religious leader challenging the established prophet; just like Moses and Korah, Michael and the Devil, and so on. Precisely as we would expect Nimrod to do to Shem.

Which is perhaps why the Bible refers to him as “a mighty hunter before the Lord,” which most commentators read as in front of, as in eclipsing, the Lord. But I’ve never really been convinced of that, although I am guilty of repeating it from time to time.

Because it’s interesting that the Bible never calls out his idolatry, though he certainly was guilty of it; the Bible chooses instead to condemn him for being “before the Lord”; what’s odd about that is it was generally a good thing to be “before the Lord”; compare to Exodus 28:30, Genesis 19:27; but not for those who don’t belong there:

Leviticus 10:1-2 Nadab and Abihu, the sons of Aaron, each took his censer, and put fire in it, and laid incense on it, and offered strange fire before Yahweh, which he had not commanded them. And fire came forth from before Yahweh, and devoured them, and they died before Yahweh.

Thus, commentators are wrong to try to force “before the lord” to mean eclipsing; that wasn’t the problem at all. The problem was a “mighty hunter” who had no business trying to be the priest-king in the first place!

That job was reserved, until the time of Moses, for the firstborn sons (at which point the Levites became the substitute firstborn sons). And Nimrod was very clearly not a firstborn (Genesis 10:7-8); it reads like he is the youngest, actually.

As is clearly exhibited in the text, this upstart believed himself better qualified to lead the human race than the appointed Lord of Aratta. This, above all, was Nimrod’s sin. And by doing this, the Weidner Chronicle tells us, Enmerkar destroyed the people of Uruk.

ARCHAEOLOGICALLY INVISIBLE

This means that the famous “priest-king of Uruk,” whom we met a few chapters ago, did not invent the post; he was usurping the post, trying to transfer it from the Indus to Uruk. Which is why he conducted such a world-wide publicity campaign underlining his shepherd-like characteristics and the awesomeness of Uruk. Which mostly worked.

But the idea of a shepherd-ruler, a priest-king, was not invented by the Sumerians, much later to inspire captive Jews in Babylon, then to ultimately be appropriated by Jesus to become the “good shepherd,” as many scholars would have us believe.

On the contrary, the imagery of a shepherd certainly was embodied by Noah and the righteous leaders after the flood; the first king of the Sumerians explicitly was given that title by “the assembly of the gods,” for we find Etana called in the SKL “the shepherd, who ascended to heaven and consolidated all the foreign countries.”

Presumably, when Shem (or whomever) told Etana he could lead Kish, he was given a speech that went something like the speech Jesus gave the disciples; which became the pattern for the “archaeologically invisible” rulers of Aratta:

Luke 22:25-26 He said to them, “The kings of the nations lord it over them, and those who have authority over them are called ‘benefactors.’ But not so with you. But one who is the greater among you, let him become as the younger, and one who is governing, as one who serves.”

It’s worth mentioning that Etana is likewise “archaeologically invisible,” as were most of his successors in Kish down to nearly the time of Enmerkar. That might be because they are just so far back in time… or it might be that they just didn’t exploit the people in the same way as later kings who were shepherds in name only.

So when Enmerkar came along, he consciously copied the form of priest-king from the legitimate rulers of the human race, Noah, Shem and Arphaxad; they were not kings, but elders, ancestors of all mankind who led by right of primogeniture (firstborn-ness).

But Nimrod was not a firstborn, yet felt himself entitled to rule. He therefore had to conduct a campaign to delegitimize his elders by casting himself as the favorite of a lovely new goddess whose temple he built – Inanna. He was her firstborn, her chosen husband.

Once in power, Enmerkar blurred the line between the priest-king and an actual king, being called Lugal, king, several times in the saga of Aratta. And when he eventually lost her favor and died in battle, Lugalbanda replaced him as king – the first known king to have “lugal,” king, in his name.

The first of many “kings of the gentiles.”

RIGHTEOUS PRIEST-KINGS

We can see a common thread in the government of the early NT Church, the Hebrews of Canaan and the Arattans of Indus; for we see in each the identical form of rule-by-elders who are leading-as-a-shepherd, serving the people, not being served by them.

1 Peter 2:9 But you are a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation …

Revelation 5:10 and made us kings and priests to our God, and we will reign on earth.

Most people read over these and miss the obvious fact that the promise to the saints is to become priest-kings in precisely the same way as Noah was. To be shepherds over the people in precisely the way Shem appointed Etana to be. Because that is, and always has been, God’s ideal.

Which is why Samuel did not waste time and money on ego projects to have massive vases carved of precious materials with his exploits on them. Nor did David; Saul did, after conquering the Amalekites and taking the forbidden spoils, and it was that act – the creation of a monument to his victory – which immediately preceded his rejection by God as king:

1 Samuel 15:12 Samuel rose early to meet Saul in the morning; and it was told Samuel, saying, “Saul came to Carmel, and behold, he set up a monument for himself, and turned, and passed on, and went down to Gilgal.”

This monument has never been found; perhaps it was destroyed by Samuel, who knows; but it shows that righteous leaders will be difficult to find in the archaeological record; whereas we find evidence for the priest-king of Uruk from Egypt to Turkey to Iran. So Enmerkar was “visible,” and Samuel, David, and Moses… weren’t.

Just as it was in the first century church; there are no giant stone monuments to Paul, Jesus, or Peter; (not in their lifetimes, anyway). Little to prove that they even existed, except the writings that were preserved by their followers, giving room for skeptics to doubt that there were any such people as Jesus and the apostles.

When we first find archaeological proof of early Christian individuals, it is when the church has already become so unrighteous as to be unrecognizable as compared to the Bible – because those men who left us monuments were, by definition, not good shepherds.

Likewise most historians believe David did not exist, and that there certainly were not judges for 450 years after Joshua. The only clear mention of David by name that has been found in the archaeological record was a monument put up by Moabites, an enemy nation, about him.

So we would expect there to be little about the shepherd-king David, because he was expected to be, as Saul, “little in his own sight” (1 Samuel 15:17). And men who think little of themselves do not leave an archaeological footprint like the leaders of pagan cultures who believe themselves to be gods.

Which brings us full circle to the invisible leaders of the Indus, who nonetheless must have existed simply because no society could possibly be so coordinated, so well planned, without a strong and organized governmental structure at the helm.

And yet we find no ego-buildings in the Indus, only public works, public baths, public roads and other things for the betterment of society. Proving that the leaders of the Indus, almost alone in all of history, actually treated that leadership as a responsibility to serve, they didn’t just say that on their monuments and Twitter accounts.

Thus, the Indus Valley leaders were shepherds of their people, leaders who guided in what they believed was the way God wanted them to go. It is clear from the civilization that the people were put before the elders, as the head of any house places his family’s welfare before his own.

And these were literally the ancestors of all their citizens.

So the only archaeologically visible sign of Arphaxad you will probably ever find, is his family; the name “Iran” on the world map – Iran, Aryan, Arattan, Arphaxad.

One last fun fact: the Hindu word Aratta is related to Arasthra which means “without a king.”

JUST WEIGHTS AND THE NEED FOR WRITING

If the Indus people were indeed the ancestors of the Hebrews of the Bible, it stands to reason they shared many of their values, not only about leadership; so Shem, whose God was Yahweh, would have valued a standardized system of weights across his family’s inheritance:

Deuteronomy 25:13-15 You shall not have in your bag diverse weights, a great and a small. You shall not have in your house diverse measures, a great and a small. You shall have a perfect and just weight. You shall have a perfect and just measure, that your days may be long in the land which Yahweh your God gives you.

Thus, the consistency and standardization of the weights in the IVC culture makes perfect sense; as does their consternation at how long they remained the same, literally hundreds of years unchanged. Not surprising, since Shem lived 500 years after the flood to keep things standardized.

In Mesopotamia, comparable standardized systems of weights and measures, on a different standard, were in use by the twenty-third century BCE. These were the result of the standardization of a number of different preexisting systems by the newly unified Akkadian state, and further official standardization was required under the Ur III dynasty after a period of political disintegration had undermined the application of an official standardized system. In contrast, the Indus system of weights and measures was apparently standardized from the start, again suggesting the unity of the Indus state and the existence of a central authority. (Ancient Indus Valley New Perspectives, McIntosh)

Furthermore, unlike other cultures, the Harappans do not seem to have “evolved” their measuring system from more primitive forbears; because they had a preexisting system of weights and measures that they brought over with them from the flood… they measured the Ark in cubits, after all.

Which oddly enough helps to explain one of the great mysteries of the Indus civilization; the relative absence of written language. They have their own unique script, apparently unrelated to the Sumerian cuneiform; but they did not seem compelled to right down stories, histories – not even taxes and contracts.

One of the reasons their script has never been translated is precisely because there are so few inscriptions, and the ones we have are quite short – the longest is about 20 characters. So why, in comparison with the contemporary Babylonians, did they write so little?

It’s not like they didn’t have regular contact with the Sumerians, who explicitly introduced them to their cuneiform writing in ELA, as we have already seen. So they knew how to write, but they simply didn’t see the point? Why?

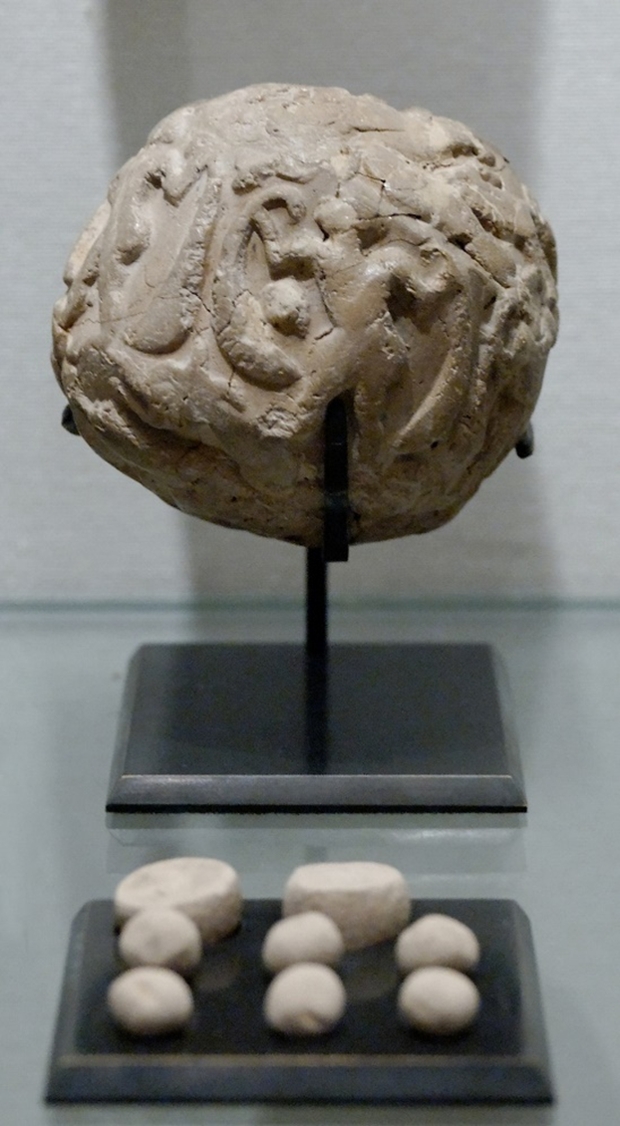

Well, think about it. All scholars agree that writing was developed in order to keep track of the flow of goods, taxes, and boundaries. The earliest examples we have are of bullae, lists of goods sealed inside of a clay ball, stamped outside; literally a bill of lading, to prevent any disagreements, theft, or outright fraud between shipment and delivery. And that’s all well and good… if it’s necessary.

Well, think about it. All scholars agree that writing was developed in order to keep track of the flow of goods, taxes, and boundaries. The earliest examples we have are of bullae, lists of goods sealed inside of a clay ball, stamped outside; literally a bill of lading, to prevent any disagreements, theft, or outright fraud between shipment and delivery. And that’s all well and good… if it’s necessary.

But what if it wasn’t?

Leviticus 19:35 You shall do no unrighteousness in judgment, in measures of length, of weight, or of quantity.

What if merchants weren’t trying to cheat their customers, employees weren’t stealing out of the order, and customers weren’t trying to claim fraud to get a better deal? If a handshake was good enough, and righteous judges were on hand to resolve disputes fairly… writing would only be necessary when dealing with outsiders.

Hence… the Indus would not have needed writing hardly at all, compared to the clearly untrustworthy and fraudulent Sumerians like Ea-nasir, the sketchy copper seller with bad reviews who most people are familiar with from his going viral on Instagram a few years back.

As for the other uses of writing, for recording history and storytelling, if the Bible’s claims about the longevity of this particular lineage are true then writing would not be needed to preserve information, since the guy living for 500 years could simply tell you himself. Indeed, the Bible explicitly connects just weights and measures to long life as quoted in Deuteronomy 25:15 above.

So the very fact that writing existed, yet never developed despite contact with Sumer and exposure to its potential uses, by itself proves it was not desirable on a large scale. And the simplest explanation for that is… the sons of Arphaxad were more righteous than the sons of Cush. Which we already know to be true.

Looked at in this light, the shocking oddities of the culture of the Indus valley, with its lack of monuments, temples, palaces, writing, warfare – all are exactly what we would expect the culture of the Arphaxadites would have been. And which happens to likewise agree with what we see the Arattans doing.

And as one last proof; the lineage of Abraham was composed of the firstborn sons of the firstborn sons of the firstborn sons; with the attendant expectations of being blessed with the best of the best. And the Indus Valley is exactly that.

It is a land that the Sumerians described as having gems literally growing on trees, with leaves made of lapis lazuli. Wealthy beyond compare in the ancient world.

Nor is it only mineral wealth; the Indus Valley floods are far less dangerous than in Sumer, and far more predictable; in fact, they flood not once, but twice a year – giving two harvests compared to Sumer’s one.

The weather is milder, more kinds of crops grow, and resources of all kinds are better. On this criteria alone there cannot be any other possibilities for the inheritance of the righteous firstborn of Noah and his offspring.

Araphaxad settled in the Indus Valley because it was the only place good enough for the firstborn son of the firstborn son of Noah.