For much of the last 2,000 years, archaeologists, saints, and crusaders have sought relics of the true cross. And throughout that time, many fragments of the true cross have been found – or were believed to have been found. Someone once quipped that if all the fragments sold as pieces of the true cross were gathered up, it would be enough to build a fleet of ships.

That’s probably not true, as the fragments most churches claim to have are no more than splinters, but still – what was the true cross like? You probably picture the standard Latin cross, shaped like a lower-case “t”, with or without a bloody Jesus hanging from it.

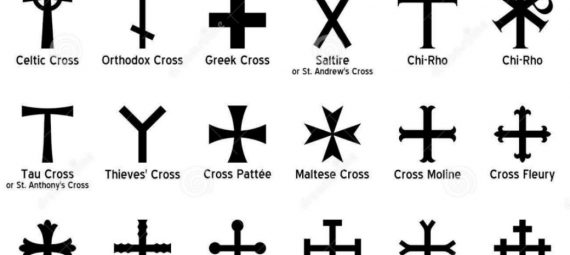

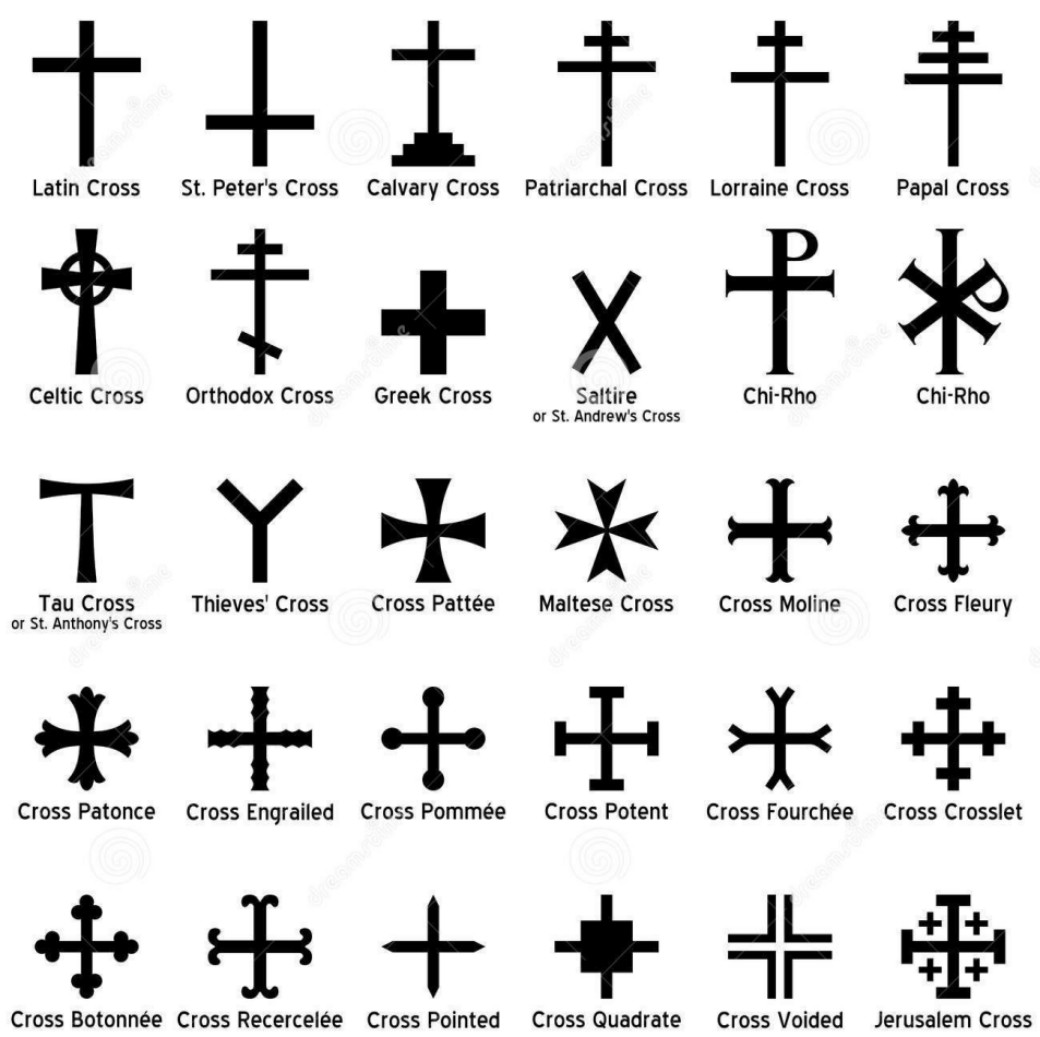

But Christians around the world disagree violently over the shape of the true cross of Christ, with a wide variety of crosses being used as Christian symbols. So how can we know which one is the real one?

But Christians around the world disagree violently over the shape of the true cross of Christ, with a wide variety of crosses being used as Christian symbols. So how can we know which one is the real one?

While certain crosses are favored candidates among scholars, there is no clear consensus as to which was the “accurate” cross of Christ. The general trend is that western Christianity (Roman Catholics and Protestants) favor the Latin cross, while Eastern Christianity (Greek, Russian, and Slavic Christians) favor the Greek cross or some form of it.

Who is right? Can all these crosses be the true cross? Certainly not! No more than one of them can be the true cross and maybe not even that one!

THE CRUX OF THE MATTER

So we need to find what the true cross looked like. Don’t be so certain you already know the answer! “Knowing” is a very dangerous thing (1 Corinthians 8:2).

But before we get into what the Bible says on the subject, I want to examine the word “cross” itself. “Cross” comes from the Latin word crux which means… well, it means “cross”. But what does THAT mean?

In our English language today, you lay beams across one another. One line crosses the other. These uses come from the same Latin word crux, which – today – means exactly the same as our English words – two intersecting lines!

Therefore, you’d think that would settle the question and eliminate, say, the Orthodox cross above (which has four intersecting lines!). Alas, it’s not that simple because the meaning of words can change over time. So let’s study what the word crux (and therefore, cross) originally meant in Latin.

Many of these quotes will come from the Catholic Encyclopedia, “Archaeology of the cross and crucifix” (henceforth, CE). No organization has spent more time and money trying to establish this question, and while I may question their conclusions, their research is excellent. There’s a lot of Latin and lengthy sources, so I’m going to trim some of that – you can read the full version on their website at http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/04517a.htm

Many of these quotes will come from the Catholic Encyclopedia, “Archaeology of the cross and crucifix” (henceforth, CE). No organization has spent more time and money trying to establish this question, and while I may question their conclusions, their research is excellent. There’s a lot of Latin and lengthy sources, so I’m going to trim some of that – you can read the full version on their website at http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/04517a.htm

According to them “The penalty of the cross goes back probably to the arbor infelix, or unhappy tree, spoken of by Cicero… This primitive form of crucifixion on trees was long in use, as Justus Lipsius notes” (CE).

Justus Lipsius was a 16th century researcher who attempted to answer the same question we’re asking, and drew up 16 different possibilities for the shape of the true cross of Christ.

The version referenced by this passage was called the crux simplex (simple cross, meaning a straight pole). The CE notes that the primitive or earliest form of crucifixion probably followed this pattern (Lipsius’ own drawing at right), by tying, nailing, or impaling a victim on a pole or tree.

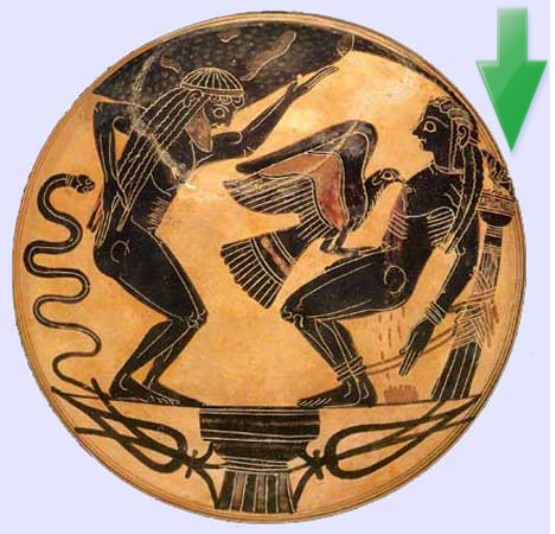

“Such a tree was known as a cross (crux). On an ancient vase [similar scene pictured lower right, arrow highlighting the “cross”] we see Prometheus bound to a beam which serves the purpose of a cross… Certain it is, at any rate, that the cross originally consisted of a simple vertical pole, sharpened at its upper end” (CE).

“Such a tree was known as a cross (crux). On an ancient vase [similar scene pictured lower right, arrow highlighting the “cross”] we see Prometheus bound to a beam which serves the purpose of a cross… Certain it is, at any rate, that the cross originally consisted of a simple vertical pole, sharpened at its upper end” (CE).

Note that a tree upon which evildoers were tortured was called a crux (cross). This is important because it means that the word “cross” did NOT originally imply two beams at right angles!

In all modern languages, including “modern” Latin, we have a deeply-rooted concept that “cross” and “crux” have always meant “two intersecting lines”. Today we use the word to refer to railroad crossings, chickens crossing roads, and parallel lines which never cross. But that’s not what the Latin word meant around the time of Christ!

“[Crux was] frequently used in a broad sense. Speaking of Prometheus nailed to Mount Caucasus, Lucian uses the substantive and the verb [forms of crux] and, the latter being derived from that which also signifies a cross. In the same way the rock to which Andromeda was fastened is called crux, or cross.” (CE).

This awkwardly-phrased quote basically says that Lucian called the mountain the mythical Prometheus was nailed to a cross. In the same way another writer called the rock to which Andromeda was tied a cross!

These two images are late Renaissance art depicting the “crosses” to which Andromeda and Prometheus were bound. This is according to the most cross-adoring organization on the planet, the Catholic Church. So you see, the word “cross” says nothing about the specific shape of the instrument of torture – although it does usually imply a pole of some kind.

So had Andromeda said to you “take up my cross and follow me”, she would have meant pick up this rock! She would not have meant pick up this ✝ cross! So had I said to you in Latin “Jesus was crucified”, that would not necessarily have meant “nailed to a ✝ cross”! It could have, but more often it would mean “nailed to a pole”!

“The Latin word crux was applied to the simple pole, and indicated directly the nature and purpose of this instrument, being derived from the Latin verb crucio, “to torment, to torture” (CE).

As hard as it is to believe, these sources say the word “cross” was in no way descriptive of Jesus’ instrument of torture! Because crux is derived from a root word that means simply “to torture”!

How is that possible? Why call it a cross if it wasn’t… you know… a cross? Because a “cross” simply meant “instrument of torture” until after people started believing that Jesus was tortured on a ✝. That powerful association swamped all other meanings of “crux”!

It was the strength of the apostate church’s belief that Jesus was killed on a ✝ which CREATED the association between crux and the ✝ cross; there was no clear association with that particular method of torture until long after the death of Jesus!

But originally, during the time of Christ and for at least a century afterwards, crux could mean any “instrument of torture”, because it was derived from the Latin verb crucio, meaning “to torture”! NOT meaning “to cross”!

Consider the phrase “this is excruciating”. This comes from the same Latin root crucio. Does that mean “this is like being tied to a cross” in English? Or does it simply mean “this is painful like torture”!

Likewise, “crucify” originally conveyed “torture”, and nothing else. Later, it meant torture on a tree or pole, in a wide variety of possible ways which is what it should still mean today! Still later, with the rise of Christianity, it came to mean tortured on a ✝ just like Jesus was! But that doesn’t mean that’s what Jesus was actually tortured on!

So we call ✝ a cross because most Christians believe that Jesus was killed on a ✝. But the fact that it was called a cross does not prove it was a ✝ cross! It could just as easily have been a “❘” cross!

THE HANGING TREE

Originally a generic “instrument of torture”, the Latin crux frequently referred specifically to the “unhappy tree” or “ill-omened (unlucky) tree”. Thus Cicero said “hang him to the ill-omened tree” (Cicero, 54 BC, “For Rabirius” 4.11). This was sometimes a living tree, but more often referred to a single, upright pole.

This is very reminiscent of what Peter says of Jesus “Who his own self bare our sins in his own body on the tree” (1 Peter 2:24). Joshua did this to the body of a pagan king after he was executed:

Joshua 8:29 (BBE) And he put the king of Ai to death, hanging him on a tree till evening: and when the sun went down, Joshua gave them orders to take his body down from the tree…

According to God’s commandment, the Hebrews killed the victims first and hung the bodies on a tree or pole to posthumously humiliate them. It was a form of shaming, but not a form of torture (Deuteronomy 21:22-23).

There is no reason to believe that the king of Ai was hanged on a cross. The Hebrew word ets simply means tree. It can be used to mean things made from trees – poles, planks, or even an erected gallows (see Esther 5:14, 8:7, etc.). But when it means that the context tells us, like Esther does! Otherwise, it must be read as simply “tree” or “pole”.

Since Jesus carried His cross – His tree – it is obvious He was not tied to a living tree, but one that could be dragged along (John 19:17, etc.). Thus, a pole cut from a tree. This doesn’t prove there wasn’t a crossbeam, it simply means we have no reason to believe there was.

Likewise in the NT, it frequently refers to Jesus being hung from a tree (Acts 5:30, 13:29, etc.). Galatians 3:13 specifically quotes Deuteronomy 21:22-23, above, using the Greek word xulon. This word means, like the Hebrew word ets, tree. By extension, things made from trees. You can see how the word is used in Revelation 22:2, 1 Corinthians 3:12, and Acts 16:24 to give you an idea of the different uses.

So while the word in no way implies a cross, it is not impossible that it was one – however the simpler reading is just “stake”, as Jesus used it “…Are ye come out, as against a thief, with swords and with staves <xulon> to take me?” (Mark 14:48).

STAUROS

We have proved that cross and crux mean “instrument of torture” and ets and xulon mean “pole”, “stake”, or something made of wood. But we have avoided the primary word translated “cross” in the NT, which is the Greek word stauros.

So when it says that Jesus was nailed to a cross, the actual word inspired by God was “nailed to a stauros”. But what exactly does that word mean?

“Stauros denotes, primarily, ‘an upright pale or stake’. On such malefactors were nailed for execution. Both the noun and the verb stauroo, ‘to fasten to a stake or pale’, are originally to be distinguished from the ecclesiastical form of a two beamed ‘cross’.” (Vine’s Expository Dictionary of New Testament Words, 1940, by W.E. Vine)

In other words, stauros did not mean cross until the church decided Jesus was nailed to a two-beamed cross! Just like crux!

“Originally Greek stauros designated a pointed, vertical wooden stake firmly fixed in the ground. Such stakes were commonly used in two ways. They were positioned side by side in rows to form fencing or defensive palisades around settlements, or singly they were set up as instruments of torture on which serious offenders of law were publicly suspended to die (or, if already killed, to have their corpses thoroughly dishonored).” (The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, volume 1, page 825).

The Gentile nations were not so compassionate as God’s law which killed the evildoer first. Other nations delighted in making their captives suffer as much as possible. The victim could be tied, nailed, or impaled on the pole in a variety of horrible and sadistic ways. Upon the fall of Jerusalem, Josephus describes the many imaginative ways the Romans crucified the Jews…

“So they were first whipped, and then tormented with all sorts of tortures, before they died, and were then crucified before the wall of the city. This miserable procedure made Titus greatly to pity them, while they caught every day five hundred Jews; nay, some days they caught more…. So the soldiers, out of the wrath and hatred they bore the Jews, nailed those they caught, one after one way, and another after another, to the crosses [stauros], by way of jest, when their multitude was so great, that room was wanting for the crosses, and crosses wanting for the bodies.” (Josephus, wars of the Jews, chapter 11)

The great shortage of wood mentioned here and elsewhere in Josephus makes it highly unlikely they would waste further wood creating a cross-beam. Particularly when single poles, perhaps spaced closely together, would allow much more efficient use of wood – victims could be nailed to multiple poles in creative and humiliating positions which the calloused Roman soldiers found amusing. Thus, rather than a field of Latin crosses outside Jerusalem, this was a field of closely spaced stakes used with all the cruelty of which men are capable of imagining.

The words translated “crosses” and “crucified” in Josephus are, as in the Bible, various forms of the Greek word stauros. A word meaning simply pole or stake at that time (70 AD).

ROMAN CRUCIFIXION

At some point, the Romans began using cross-bars on their crux-poles. “To this upright pole a transverse bar was afterwards added to which the sufferer was fastened with nails or cords, and thus remained until he died…” (CE). The bar was sometimes lower, sometimes higher, sometimes on top to form a T.

The problem is, no one quite knows when this changed, or if it ever became the exclusive method. It seems like such an easy question to answer – how did Romans crucify other people? If this was a widespread practice, and it was, then surely there would be many descriptions of their use.

And there are – the problem is, all historians, even the most fanatical believers in the ✝ admit that the Romans practiced many forms of crucifixion during and after the time of Christ. As has been shown, there was no one universal way to use the word crux or stauros. Just like there is no one specific meaning for “and they tortured him”!

“He was crucified” could mean the victim was tied or nailed to, impaled on, or hung from a tree, post, or gallows, or in a pinch a building, cliff, or boat mast; with or without a crossbar, with or without a seat, before or after death, etc.

“At times the cross was only one vertical stake. Frequently, however, there was a cross-piece attached either at the top to give the shape of a T (crux commissa) or just below the top, as in the form most familiar in Christian symbolism ✝ (crux immissa). The victims carried the cross or at least a transverse beam (patibulum) to the place of execution, where they were stripped and bound or nailed to the beam, raised up, and seated on a sedile or small wooden peg in the upright beam…” (Anchor Bible Dictionary, article “Crucifixion”).

Seneca the Younger, contemporary of Jesus, said of Roman crucifixion methods “I see before me crosses not all alike, but differently made by different peoples: some hang a man head downwards, some force a stick upwards through his groin, some stretch out his arms on a forked gibbet” (Seneca the Younger, “To Marcia on Consolation”).

And unfortunately, the Bible is completely silent regarding a precise description of the stauros to which Jesus was crucified. It tersely says “and they crucified him” (Mark 15:25). There are other details of course, like the sign above His head – but nothing that conclusively proves the shape of the cross.

CHRISTIAN BELIEF IN THE ✝

“It is probable, though we have no historical evidence for it, that the primitive Christians used the cross to distinguish one another from the pagans in ordinary social intercourse…. Such observations throw light on a peculiar fact of primitive Christian life, i.e. the almost total absence from Christian monuments of the period of persecutions of the plain, unadorned cross” (CE).

Notice that they believe this while admitting they have absolutely no evidence. If the cross is the true Christian symbol, why did the earliest Christians – those who knew Jesus, knew the apostles, knew their disciples – not use it?

“During the first two centuries of Christianity, the cross was rare in Christian iconography, as it depicts a purposely painful and gruesome method of public execution and Christians were reluctant to use it.” (CE)

Why, when the modern Christian world proudly displays this “purposely painful and gruesome method of public execution”, did the original Apostolic Christians hesitate to use it? Wouldn’t THEY know what Jesus wanted better than modern preachers or third-century apostate Christians?

“It is not, therefore, altogether strange or inconceivable that, from the beginning of the new religion, the cross should have appeared in Christian homes as an object of religious veneration, although no such monument of the earliest Christian art has been preserved.” (CE)

Do you notice the inherent assumption there? “We have no proof, but this is what must have happened because this is how we do it today!” While the apostles still lived, there was conspiracy and deception and false doctrine in the church (2 Thessalonians 2:7). While John was still alive, he was being put out of churches he raised up! (3 John 1:9-10).

The so-called church fathers (dating from 150 AD and onward) unanimously believed the cross to be either a T or a ✝ but the Bible doesn’t say and there is no proof from the first century! So if John was being put out of his own church by false Christians less than 50 years after the death of Christ, how much can we rely on third-hand evidence dating 100 or 200 or more years after the crucifixion?

We know the Catholic “church fathers” embraced many false doctrines not found in the Bible. They were, in fact, the systematic creators of the false gospel. So how can we rely on their testimony, which we know was based on hearsay at best, and pagan superstition at worst? No evidence from the first century exists simply because the true Christians didn’t revere the cross and were “reluctant to use it”!

“The early years of the fifth century are of the highest importance in this development, because it was then that the undisguised cross first appears. As we have seen, such was the diffidence induced, and the habit of caution enforced, by three centuries of persecution, that the faithful had hesitated all that time to display the sign of Redemption openly and publicly.” (CE)

The reason given by the CE – fear of persecution – is one possible interpretation of these facts. The other way to interpret them is that the earliest Christians did not worship the cross and did not believe Jesus was crucified on a ✝!

MERGE AND HARMONIZE

So based on the gospel description, based on history, and based on the words themselves the conclusion has to be that we don’t know. Later, apostate historical accounts favor the ✝ cross, while the meaning of the words themselves favors the simple pole or stake.

Linguistically, there is absolutely no reason to believe it was a ✝ cross, but it’s not impossible from the text that it could be. Most Christians take their cue from descriptions written 200 years after the fact by historians we know had already departed from the truth of the gospel.

So what do we do? What we always do! Merge and harmonize! This event had been prophesied for thousands of years, and Jesus was fulfilling OT symbolism with almost every step He took. So even though the NT doesn’t specifically describe the cross, there are enough clues in the OT to allow us to form a solid conclusion.

Jesus described His cross as follows “And as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, even so must the Son of man be lifted up” (John 3:14). This means that when Jesus was lifted up on the cross, it would be in the exact same way as Moses lifted up the serpent! And on the exact same type of stauros! So read that story in Numbers 21:8-9.

Precisely why this event happened and what it means is interesting, and can be explained, but for now focus on the clear description of the event! You do not need a cross bar to put an armless serpent on a stauros! You need only a POLE to put it on, as the Bible describes, which agrees with the simplest meaning of the NT stauros!

See how, by allowing the Bible to interpret itself, we can solve problems? Nearly 1,000 years later when Israel was sinning, a good king came along and destroyed this same brass serpent:

2 Kings 18:4 (YLT) …and beaten down the brazen serpent that Moses made, for unto these days were the sons of Israel making perfume to it, and he calleth it ‘a piece of brass.’

The original language (left untranslated in the KJV as nehushtan) implies the diminutive, as in “that worthless little piece of brass”. Not unlike Paul’s phrasing in 1 Corinthians 13:1, if a man doesn’t show love he is “as sounding brass”.

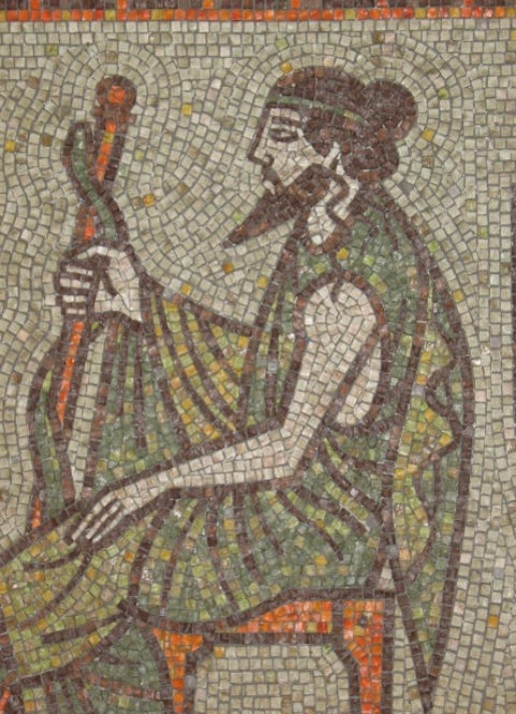

For our purposes, however, this seems to be a single brass casting, one large enough to be seen from some distance but not so large it couldn’t be lifted up and then transported across the wandering in the desert. Interestingly, the description of a healing serpent on a pole is eerily like the Greek myth of the healer god Asclepius (near right), who is always pictured with a serpent wrapped around a staff. Made of brass, the pole would have looked like this (far right).

For our purposes, however, this seems to be a single brass casting, one large enough to be seen from some distance but not so large it couldn’t be lifted up and then transported across the wandering in the desert. Interestingly, the description of a healing serpent on a pole is eerily like the Greek myth of the healer god Asclepius (near right), who is always pictured with a serpent wrapped around a staff. Made of brass, the pole would have looked like this (far right).

But there is one final association to explore – remember, always merge all the scriptures on a subject before you draw a conclusion!

Remember the story in Exodus 7:10-12. This miracle in Egypt showed the transformation from a pole to a serpent, it fighting with and eating other serpent-rods, and becoming a staff again. The details of why and how this miracle happened are again, not the point – the point is a clear association with a serpent and a staff or stake.

So when Moses made a brass serpent on a stake it would have evoked memories of that miracle, as well as foreshadowing Jesus’ death on that same type of stake! When Jesus would be lifted up above the people, as this serpent was, and swallow up Satan’s serpents just as Aaron’s rod had!

Moses fled from that serpent! (Exodus 4:3). But Jesus bruised its head (Genesis 3:15) and destroyed the works of that serpent (1 John 3:8, Hebrews 2:14, etc.) just as Aaron’s rod did! And He did that BECAUSE He was lifted up just like the brazen serpent, which made it POSSIBLE to cast out the devil (John 12:31-34)!

THE STAKE OF CHRIST

So while the historical record is ambiguous or unreliable, and while the linguistic arguments are not convincing… as always, the Bible itself contains the clear answer. Jesus was crucified on a stake. It simply could not have been a ✝ – Moses hung the brass serpent on a POLE, like the staff of Aaron that became a serpent, just as the inspired record tells us that Jesus was nailed to a stauros, a stake!

Any other conclusion is forcing a meaning into the Bible based on your own belief, which is precisely why no one can understand the Bible today. They seek to make the scriptures say what they already believe to be true.

I will continue to use the word cross, just as the Bible translations also use the English word cross, because the word means, and has always meant, “torture-pole” in English, Latin, and Greek. So it is not incorrect to use the term if you know what it really means.

But if it means ✝ to you, then it is incorrect to use the term, and it would be better for you to emphasize stake or pole until you are comfortable with the idea. It’s very hard to unlearn wrong ideas, as you are no doubt realizing.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

Why does it matter so much? Particularly since it’s so hard to be sure, who really cares whether it was a ✝ or a T or a “❘”? The False Cross article will answer that question in great detail. But for now, let’s ask the Catholics themselves where the sign of the cross – by that I mean, the sign of two intersecting lines – came from?

“The sign of the cross, represented in its simplest form by a crossing of two lines at right angles, greatly antedates, in both the East and the West, the introduction of Christianity. It goes back to a very remote period of human civilization… the cross was originally not a mere means or object of ornament, and from the earliest times had certainly another – i.e. symbolico-religious – significance.” (CE)

What they’re saying, while trying not to say it, is that pagans worshiped the cross thousands of years before Christ was crucified on the stauros.

“The primitive form of the cross seems to have been that of the… swastika. At successive periods this was modified, becoming curved at the extremities, or adding to them more complex lines or ornamental points, which latter also meet at the central intersection.” (CE)

“The swastika is a sacred sign in India, and is very ancient and widespread throughout the East. It has a solemn meaning among both Brahmins and Buddhists… It is also, according to Milani, a symbol of the sun… and seems to denote its daily rotation…. taking the Sanskrit word [swastika] literally… it would mean ‘sign of benediction’, or ‘of good omen’ (svasti), also ‘of health’ or ‘life’.” (CE)

So in Sanskrit (ancient Indian), the word swastika originally meant “sign of blessing”, or “sign of life”.

“Another symbol which has been connected with the cross is the ansated cross (ankh or crux ansata) of the ancient Egyptians… From the earliest times also it appears among the hieroglyphic signs symbolic of life or of the living…” (CE)

Now the fascinating thing is that to the ancient Egyptians, the ankh-cross was “a sign of life”. To the ancient Indians, the word swastika literally meant “a sign of life”. And if you ask any good Christian what the cross around their neck means, they will tell you “it is a sign of Jesus’ resurrection” – in short, “a sign of life”! And when the Pope makes the sign of the cross, is it not “a sign of benediction”?

So you see, it matters a great deal whether Jesus was crucified on a ✝ or a ❘ cross! Because the ✝ cross is an ancient and pagan symbol, which means to the false Christian today the same thing as the heathen cross meant to the heathen. So it’s no surprise that the Catholic Encyclopedia goes on to say…

“…largely employed during the third and fourth centuries, the swastika…. still more closely resembles the cross…. Many fantastic significations have been attached to the use of this sign on Christian monuments, and some have even gone so far as to conclude from it that Christianity is nothing but a descendant of the ancient religions and myths of the people of India, Persia, and Asia generally.” (CE)

Obviously, the Catholics ridicule this claim. Yet equally obviously, they admit they use the same sign, to which they ascribe the same meaning, as those ancient pagan religions God hated. And the conclusion they ridicule is the simple truth:

Their version of Christianity is nothing but a descendant of the ancient religions and myths of the people of India, Persia, and Asia generally. And specifically, of Babylon.

Continue to Part 2: The False Cross

Download our print friendly pdf version of this article.